Last fall I wrote a historical mystery short story and showed the first four pages to a local Writer-in-Residence. The WIR’s main advice was to turn the story into a novel. I had no clue how I’d do this and she didn’t offer suggestions, but I was intrigued by the idea.

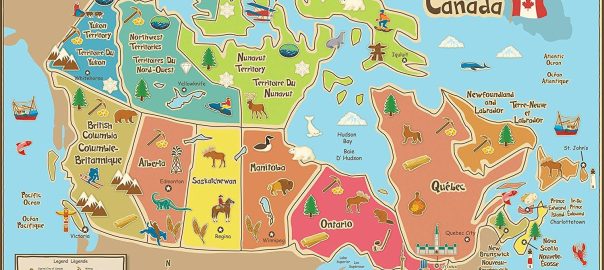

Then this spring BWL decided to publish a collection of Canadian Historical Mysteries. They assigned thirteen of their authors to write a novel set in a specific Canadian province or territory. The collection will have twelve books — British Columbia is co-authored and Nunavut/Northwest Territories will be reunited in one of the books. I’m delighted to represent my home province of Alberta.

BWL asked us to provide a working title and novel blurb, which they’ll publish in a free guidebook as advance promotion. This got me mulling ways to expand my short story, which was set in Calgary during the 1918 influenza pandemic and told through the viewpoint of a police detective. The WIR’s other suggestion was to change the protagonist to a character who was present at the victim’s death, to make that aspect of the story more immediate. One of the suspects appealed to me as a point-of-view narrator, but if I let readers enter his thoughts I’d lose him as a suspect. Also, while I like experimenting with male protagonists in short stories, I prefer to write female protagonists for novel-length works. This led to my idea for a new character and protagonist, the sister of that suspect. She will be motivated to solve the crime to know if her brother or someone close to him is guilty of murder.

I plan to keep my detective as a secondary narrator. His investigations and personal story will increase the material. In the short story, he had a romantic interest in a co-worker. For the novel I’ll shift his interest to my heroine to enhance their relationship. She’s married, but her husband has been overseas for four years, fighting in The Great War, and she’s changed during that time. Her feelings for the detective will create lots of conflict for them both.

My other idea is to add a new suspect to this longer story; a man who opposes the war. The victim and my heroine’s brother are injured veterans, who received an early discharge. WWI officially ended November 11, 1918, in the middle of the second and deadliest wave of the influenza pandemic, but most of the Canadian troops didn’t return until the following spring. I’d like to make the war more present in the novel than it was in the short story, from the perspectives of those on the home front.

I’m satisfied these additions and changes will be enough to expand my 4,500 word short story to a 75,000 word novel, the median length of the books in the collection. More importantly, I’m eager to write the larger story to develop these characters and find out what happens to them in the new version.

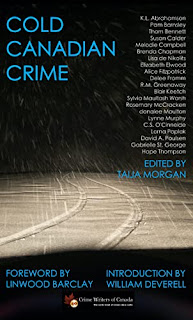

In effect, the short story is my novel outline. I’m sure much will change in the process of writing the book. Even whodunnit and why the person done it and how he or she done it are up for grabs. So if you read the short story, don’t worry about spoilers. After I showed the WIR those first pages, the short story was accepted for publication. It appears in the recently released Cold Canadian Crime Anthology, available on Amazon, Kobo, and other sites.

A new title will be one definite change for the novel. The the short story title “A Deadly Flu” was a wink at my first novel, A Deadly Fall. Two similar novel titles would create confusion.

Here’s the cover for the Canadian Historical Mysteries guidebook, which you will soon be able to download for free to read the twelve novel descriptions.

For updates, check out the BWL Canadian Historical Mysteries Page https://bookswelove.net/authors/canadian-historical-mysteries-collection/