My book launch for my new mystery novel A Killer Whisky is ten days away. I’ve spent the past month on preparation, and there’s still plenty to do.

An easy task was to create a Facebook Event Page and invite about 160 Facebook friends who live in the Calgary area. So far, nine have said they’re going. This might not seem like a lot, but some will bring a friend, not all attendees confirm, and part of the purpose is to let people know my new book is available. I drop into the Event Page daily and make occasional comments to generate interest. One friend told me my Event Page shows up regularly on his Facebook feed, possibly because he presses “like” whenever the page appears. From other “likes” to the page, I notice that friends I didn’t invite have seen it. Thus, the page becomes continuous promotion for relatively little effort on my part.

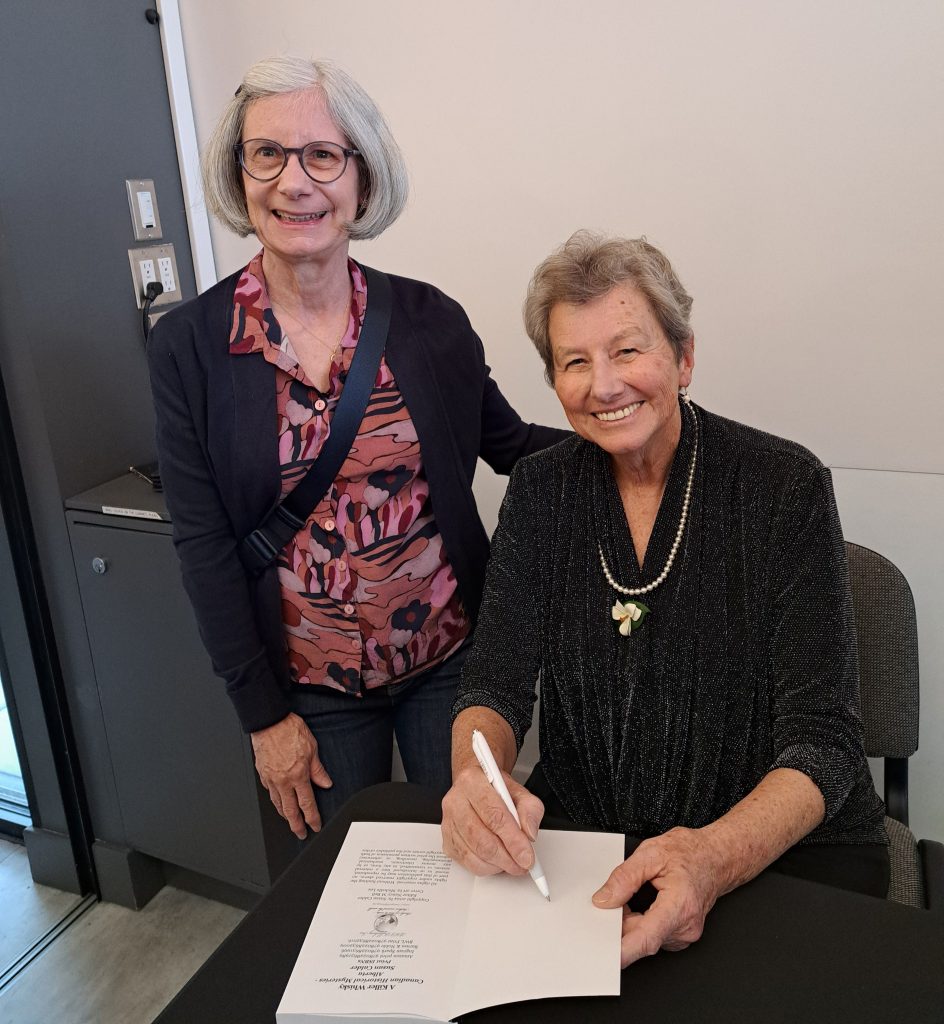

For friends who aren’t active on Facebook, I created a poster that I email to them individually. This takes more time than a mass mailout, but I think the personal approach prompts more people come. People usually reply, whether they can go or not, and it’s fun to catch up with those I haven’t seen in months or longer. I contact everyone who’s shown an interest in my writing and especially those who have attended previous launches. It helps to keep an attendance list and look back at previous launch pictures.

In addition, I’ve sent notices about the launch to my writing groups for inclusion in their weekly or monthly newsletters to members. Few people will attend as a result of these announcements, but some might buy the book and read it if it strikes them as interesting.

I’ve also started work on the launch program, which will centre on my PowerPoint presentation. I enjoying doing PowerPoints and work hard to find the right image or bullet points to compliment what I want to say. My talk will focus on my inspirations for writing A Killer Whisky, setting locations in Calgary, and the novel’s historical background – the story takes place during the 1918 Flu Pandemic, World War One, and Alberta Prohibition. I still need to create more slides and tweak existing ones to make the newspaper headlines, advertisements, photographs, and cartoons more effective.

A week before the launch, I’ll get a dress rehearsal for the PowerPoint presentation at the Pincher Creek Municipal Library, where I’ll discuss the historical events relevant to an audience in Southern Alberta. Both the Pincher Creek Author Talk and Calgary Book Launch will include readings from the novel, which I still have to select, practice, and fit into the program.

Other ingredients for the book launch event are food and drink. Since “whisky” is in the novel’s title and plays a key role in the story, I’ve pursued my idea of serving “wee drams” of whisky and whisky cocktails named for the story’s characters. A few weeks ago, I knew little about whisky cocktails other than that I’d liked Whisky Sours when I was younger. From the internet I’ve now learned about bitters, muddlers, and channel knives for making lemon twists, and I’ve found cocktail recipes that my husband and I are experimenting with this week. Our first attempt was a success! Cinnamon Maple Whisky Sour will be the signature drink for my protagonist Katharine, a Canadian patriot who supported the Great War.

Between now and the launch on March 25th, I’ll need to shop for snack platters, lemons for my mixers and twists, and door prizes with whisky, mystery, and/or history slants. I still need to finalize arrangements with my bookseller, Owl’s Nest Bookstore. No doubt myriad details requiring attention will come up. Let’s hope for no last-minute disasters, like a snowstorm – not unusual for Calgary in March – or a key person like me coming down with the flu.

Is the book launch worth all this time, effort, money, and stress?

I don’t know.

But it is fun to plan a party.

Cheers to everyone who loves writing and reading books!