Every month deserves a Blue Monday. For February, Psychology Month, here is my blog post written two years ago and revisited.

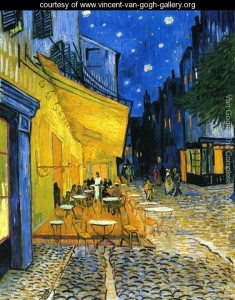

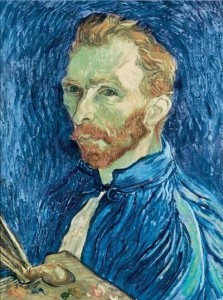

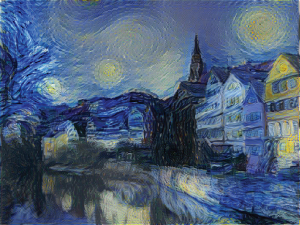

While researching a holiday to Provence, France, I stumbled upon The Van Gogh Blues: the Creative Person’s Path Through Depression by Eric Maisel, Ph.D. My husband Will and I planned to spend a week in the town of St. Remy, Provence, where the painter lived in an asylum toward the end of his life. During that time, Van Gogh painted a number of his major works, including The Starry Night.

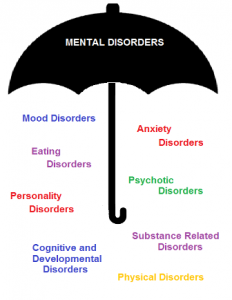

The Van Gogh Blues turned out to be less about the painter than about depression, the disease many believe he suffered from. Others claim schizophrenia or epilpsy might have been the problem that led Van Gogh to cut off his ear and ultimately take his own life.

The Van Gogh Blues turned out to be less about the painter than about depression, the disease many believe he suffered from. Others claim schizophrenia or epilpsy might have been the problem that led Van Gogh to cut off his ear and ultimately take his own life.

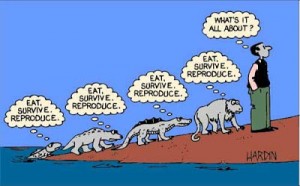

Maisel’s premise in The Van Gogh Blues is that creative people suffer from depression more than the non- creative. He offers no statistics for this. His view stems from his observations as a family therapist with a PhD in counselling psychology, a creativity coach and a creative writer who regularly contributes to Writers Digest magazine. He concludes that depression arises from the creative person’s need for meaning and his or her clash with the facts of existence. He say non-creative people don’t seek as much meaning in their lives, either due to their personality makeups or the fact they already have enough meaning. For instance, the unwaveringly religious find enough meaning through their faith.

creative. He offers no statistics for this. His view stems from his observations as a family therapist with a PhD in counselling psychology, a creativity coach and a creative writer who regularly contributes to Writers Digest magazine. He concludes that depression arises from the creative person’s need for meaning and his or her clash with the facts of existence. He say non-creative people don’t seek as much meaning in their lives, either due to their personality makeups or the fact they already have enough meaning. For instance, the unwaveringly religious find enough meaning through their faith.

It follows that the collapse of traditional religion makes depression more common today than in the past, Maisel asserts this is true, but I wonder. I also question his statement that explorers, military personnel and professional atheletes have zero rates of depression. The reason, he says, is that these occupations contain built-in action and meaning.

Depression arises, he claims, when creative people fail to work toward the meaning they need. This can be due to procrastinating, taking a job that doesn’t answer their creative needs, drinking, eating too much chocolate, anything to avoid the blank page.

And those who put in the work are bound to bump against the facts of existence. A writer’s book can’t find a publisher or it does and fails to sell. This provokes a meaning crisis that, if not handled well, leads to depression.

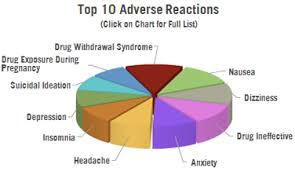

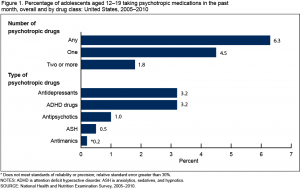

Maisel does admit that biological or psychological factors might also contribute to depression. Therefore, people shouldn’t necessarily avoid medication or therapy. But he believes these factors aren’t the primary cause.

It almost makes depression seem a positive trait, since those disinclined toward it are non-creative (lesser?) beings.