Catherine Ford’s Opinion column in today’s Calgary Herald newspaper reminded me of a radical book on mental health treatment that I read two years ago. Here’s the review of the book, which I posted at that time.

At 450 pages, Brain-Disabling Treatments in Psychiatry: Drugs, Electroshock and the Psychopharmaceutical Complex by Peter R. Breggin, MD is a big book. It’s not an easy read, which you might guess from the technical-sounding title. Breggin states at the start that his book is aimed at professionals, although he hopes it’s clear enough for non-professionals to understand. Partly for these reasons, I only read the first and last sections, along with the brief conclusions Breggin sometimes offered in the middle sections. This was still enough to convince me that of all the professional psychology books I’ve read and am reviewing this month, Brain-Disabling…is the most exciting, and the one that did the most to change my thinking on mental health treatment.

Breggin, age 79, has been a practicing psychiatrist in upstate New York for over 40 years. He claims he has never prescribed medication and has never lost a person to suicide. He disagrees with the biological model for mental illness and avoids labels such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. His approach is to listen to a patient’s life story. That is, to treat him or her as a person and not as a problem to fix.

Breggin, age 79, has been a practicing psychiatrist in upstate New York for over 40 years. He claims he has never prescribed medication and has never lost a person to suicide. He disagrees with the biological model for mental illness and avoids labels such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. His approach is to listen to a patient’s life story. That is, to treat him or her as a person and not as a problem to fix.

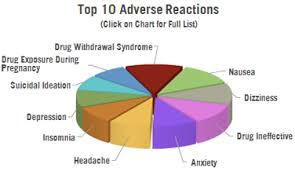

The part that threw me the most is his belief that psychiatric drugs are not only ineffective, they are harmful and work against recovery by impairing mental and emotional function. People’s belief these medications are helping them are due to the drugs’ spellbinding effect, much like the belief that you are witty and in control when you’re drunk.

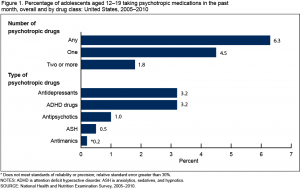

The large middle section of Breggin’s book is devoted to proving his point for each current treatment, including psychotropic drugs, Electro Convulsive Therapy (ECT or Shock Therapy) and the medications for Attention Deficit Disorder. He especially opposes the current treatment of children for ADD/ADHD and depression. He claims there is an upsurge in diagnoses for bipolar disorder today because antidepressants have caused mania in people, who are then told by their psychiatrists that the treatment has unearthed this underlying condition.

I don’t feel qualified enough to know if his arguments against these treatments are solid or not. This is a second reason I skipped over the book’s middle. A third is that I don’t need his detailed arguments to be convinced, since I favour the nurture over nature view of mental illness and can easily accept a critique of medication. Breggin states that even if it is one day proven that some disorders are due to chemical imbalances — and there is no proof for this so far — our current drugs and shock therapy aren’t the way to go.

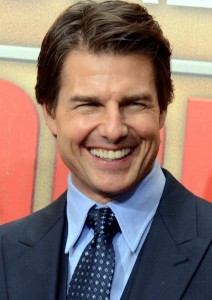

His extreme views made me Google him to find out if he’s a Scientologist, since they are notoriously opposed to modern psychiatry and its treatments. Breggin was associated with Scientology in the early 1970s. He wasn’t a member, although his wife was. Breggin broke with the the Scientologists partly because they opposed her marriage to an outsider. No doubt Scientology’s views on psychotropic medication were an attraction for him and the religion might have influenced, or at least reinforced, his thinking. Pharmaceutical companies have accused Breggin of being a Scientiologist to discredit him because he has been an expert witness in lawsuits against their products and vocal in his opposition to them.

Breggin wrote a defense of Tom Cruise’s rants on TV against psychiatry and medication. “The media would have liked to attack Tom on the grounds that he’s a Scientologist,” Breggin says. “Scientologists seem to share a number of views about psychiatry with me, including everything Tom said. In fact, I’d go further. Modern biological psychiatry is a materialistic religion masquerading as a science.”

Breggin’s credentials and clinical experience make it hard to dismiss him as a quack.  I was moved by the final section of his book, where he outlines his 20 tips for an empathetic psychiatry. He notes these guidelines could also be used in our everyday lives with colleagues and friends, and insists they have worked in his psychiatric practice, even with the most difficult and psychotic cases.

I was moved by the final section of his book, where he outlines his 20 tips for an empathetic psychiatry. He notes these guidelines could also be used in our everyday lives with colleagues and friends, and insists they have worked in his psychiatric practice, even with the most difficult and psychotic cases.

Psychosis, he says, is a “loss of connectedness to other human beings. The individual who withdraws into a fearful, self-protective, irrational fantasy responds best to being treated with kindness, respect, and the gradual building of rapport.”

It seems naïve and too simple, but could it work?