In case you missed it, here is my April 12th blog, which was posted on my publisher BWL’s website.

*

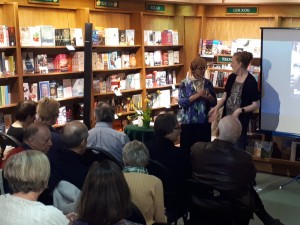

On March 26th I hosted a book launch for my new novel, To Catch a Fox. For the venue, I chose Owl’s Nest Books in Calgary because I’d held launches there for my two previous novels and I love this independent bookstore which is so supportive of local writers. You’d think launches would be old hat for me the third time around, but I always find something new to worry about. This time, in addition to reading and answering questions, I tried out a power point presentation using a system borrowed from a friend. At the last minute, I decided to rent a microphone and am glad I did. It was easier to use than I’d expected. Close to 85 people attended the launch and those at the back would have had a hard time hearing my voice, especially after it was strained from 40 minutes of talking.

|

| My friend advised me to make my book cover the first slide, for people to watch during the introductions |

For my talk, I wanted an upbeat mood despite the novel’s dark material. So I chose a travel photo theme and showed pictures from my two holidays in Southern California to research potential settings for To Catch a Fox. I found I didn’t need notes, since each slide prompted me about what to say next. My idea was to give a sense of how I worked my own travels into the story and make the settings feel more real for readers when they later encountered them in the book.

| This woman conveniently photo-bombed my picture of the Santa Monica boardwalk. Julie, my protagonist, jogs along this same boardwalk. |

Initially, I planned to save my readings from the novel to the end of the presentation. Then I realized it would be more interesting for listeners to look at a picture where the scene takes place. So I paused part-way through my talk for my first reading. I was afraid this might break the flow, but it served as a transition between my first and second research holidays.

As a non-techy person, I had to make three trips to my friend’s house to get the presentation working properly. My friend’s favourite part of the program was the cheesy apartment that Will and I rented for our first California trip. Julie and Delilah stay in this same place. Another friend who has started reading To Catch a Fox told me she’d have thought I was exaggerating the racy décor if she hadn’t seen the slide show.

| The boudoir, where Julie slept. Delilah slept in the sofa bed in the cluttered living room. |

I started writing To Catch a Fox when I got home from the first trip. After two drafts, I felt confident of my Los Angeles area details, but wanted to get a better feel for the novel’s primary setting — a fantasy retreat. All I had was a vague sense that it was about a two hour drive east of Los Angeles. When my sister-in-law suggested we join her on a cruise from San Diego, Will and I tacked on a road trip to the California interior. Our explorations wound up locating my New Dawn Retreat farther south than I’d thought, in a sparsely populated orange growing belt. We began the drive with a stop at the California Citrus State Historic Park and bought a bag of oranges. They were delicious.

This landscape below is the closest I could get to my imagined retreat. The New Dawn Retreat in my story features a broad lawn enclosed by hills, with citrus and olive cultivation on the hillsides.

For my second reading, I chose a scene set at the New Dawn Retreat.

The presentation wrapped up with questions and door prizes, which included an Owl’s Nest gift card as my thanks to the bookstore, a recently published chapbook of one of my short stories and, most exciting of all, bottles of Dawn dish detergent.

What I find most fun about book launches is seeing people from different areas of my life gathered together in one place. Friends, family, my fellow hiking and book club members, writer acquaintances, readers who’ve enjoyed my previous novels. I don’t get a chance to talk to them all, but it’s wonderful to see their supportive faces in the audience and to touch base briefly with a few.

And now, what will I do for my next launch? First I’ll have to write the book.

![41377069_1881674171911258_3873486109245702144_n[1]](http://susancalder.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/41377069_1881674171911258_3873486109245702144_n1-300x225.jpg)

![IMG_0995[2126][31274]](http://susancalder.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/IMG_0995212631274-e1553721409684-225x300.jpg)

![55752374_10156072069277724_1359071679887704064_n[1][31275]](http://susancalder.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/55752374_10156072069277724_1359071679887704064_n131275-300x225.jpg)

![celebrating-25-years-400[1]](http://susancalder.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/celebrating-25-years-4001-300x251.jpg)