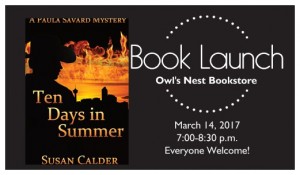

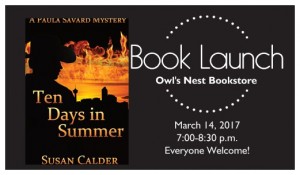

1-2-3-4 days to Owl’s Nest Bookstore. This weekend, the clocks spring forward, which means there will be light in the sky when the launch starts.

1-2-3-4 days to Owl’s Nest Bookstore. This weekend, the clocks spring forward, which means there will be light in the sky when the launch starts.

Five days to go: Owl’s Nest Bookstore.

Six days until Owl’s Nest Bookstore. The long-term weather forecast says this spell of cold and snow should end in time for the book launch day. Hey Calgary weather, it’s March. The days are getting longer already.

March 7th and there’s 7 days to go: Owl’s Nest Bookstore. Double sevens for good luck? Let’s hope.

March 7th and there’s 7 days to go: Owl’s Nest Bookstore. Double sevens for good luck? Let’s hope.

Eight Days until the launch for Ten Days in Summer at Owl’s Nest Bookstore. My recent hiking holiday in Arizona took my mind off things. Now I’m getting nervous.

Yesterday, I attended the Alexandra Writers Centre Society’s Alberta Skies Art and Book Exhibit. The event took place at the new AWCS premises in cSpace, Calgary’s new home for artists of all kinds. It drew a crowd that packed our three rooms, warming them up so much that the building custodian opened the top three windows for the first time.

cSpace is still under renovation, but the AWCS’ classrooms are already a go. Somehow, we scored the penthouse–those are our windows on the top floor (left hand side). Each classroom gets tons of light and has a view of the Rocky Mountains. What a change from our former basement location, although the setting in a sandstone school nicely continues the AWCS heritage.

Nine days to go until the launch for Ten Days in Summer at Owl’s Nest Bookstore.

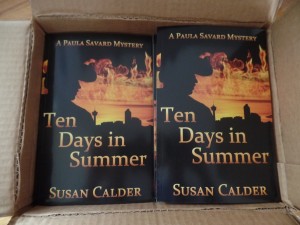

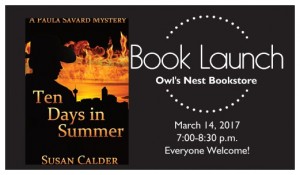

I doubt I’ll publish another book with 10 in the title, so this is my chance for a 10-day countdown to my book launch. Here it begins.

I doubt I’ll publish another book with 10 in the title, so this is my chance for a 10-day countdown to my book launch. Here it begins.

Today, from 3:00 – 5:00 p.m, I’ll be at the Alberta Skies Art Exhibit

cSpace King Edward, 1721 29 Ave SW, Calgary

Featuring Alberta Skies course participants at the Alexandra Writers Centre Society

Art Exhibition, Book Sales, Readings, & Music by the Authors/Artists, Refreshments served

Come and check out cSpace, Calgary’s new arts incubator and new location for the Alexandra Writers Centre Society. The AWCS windows are on the top floor, left hand side of this picture looking up from the dumpster — building renovations are still in progress.

Ten days to the launch of Ten Days in Summer — March 14, 7:00 p.m. at Owl’s Nest Bookstore.

In my blog yesterday, I interviewed BWL author Janet Lane-Walters. Today, read about three of Janet’s numerous published books. Janet mentions my new book and the launch for Ten Days in Summer in her blog.

The Aries Libra Connection (Opposites in Love) by Janet Lane-Walters

Jenessa is Aries, a nurse, union advocate and likes a good fight.

Eric is Libra, Director of Nursing, and believes in compromise.

Can these two find a way to uncover the underhanded events at the hospital? They’re on opposite sides but the attraction between them is strong. She’s a widow who fought to save her husband’s life during a code. She feels guilty because the love she and her husband shared had died before his death. He assisted at the code but he feels guilty since he was the one who was responsible for the short staffing the night her husband died.

Now they face falling in love and trying to solve the problems between the nurse’s union and the president of the hospital’s Board who wants a take over of the hospital by his hospital group. Is their connection strong enough to survive?

Bast’s Warrior – An alternate Egypt Story by Janet Lane-Walters

Bast’s Warrior – An alternate Egypt Story by Janet Lane-Walters

Tira flees a threat to her life and encounters two elderly women who offer her the chance to be sent to an alternate ancient Egypt with no thought of return. She has had a fascination with Egypt and can even read hieroglyphics. Once there she will be given a task. Failure could mean death. Dare she take the chance and can she find the lost symbols of the rule before an enemy finds them?

Kashe, son of the nomarch of Mero is in rebellion. His father desires him to join the priesthood of Aken Re, a foreign god. He feels he belongs to Horu, god of warriors and justice. He decides to leave home, meets Tira and joins her in the search for the symbols of the rule. Will his aid bring good fortune and will their growing love keep them from making a fatal mistake?

Previously published as The Warrior of Bast

“This engaging voyage into an ancient Egypt that includes power-hungry priests and hazardous treasure hunts entertains from page one. Familial intrigue heightens the tension, as does a kidnapping or two. The cast of characters is dynamic and complements the well-conceived plot.” ~ 4 Stars, Susan Mobley, Romantic Times Magazine

Seducing The Blakefield Sisters by Janet Lane-Walters

Part One

Seducing the Chef – Allie Blakefield, editor of Good Eatin’ wants to do a feature on Five Cuisines a restaurant across the river from NY City. Her father forbids the feature and won’t say why. She’s not one to sit back and be ruled by someone. She borrows a friend’s apartment. While leaning over the balcony she sees a handsome dark haired man doing a Yoga routine. He looks up and she is struck by the Blakefield curse. Love at first sight. The pair start a hot and heavy romantic interlude. She visits the restaurant and is recognized by Greg, the chef’s mother. The woman goes ballistic and the affair is broken. Can Allie learn what’s going on and rescue her love?

Part Two

Seducing the Photographer

Meg is sure she’s made a mistake when she agrees to pick up and Injured Steve, the magazine group’s photographer from the airport. The first moment she saw him, the Blakefield Curse took effect. She fell in love and she was a forever woman. He wasn’t. Spending time with him over the weekend only cements her feelings. She has rules of life and she breaks everyone of them even the new ones she added that weekend.

Steve has been intrigued by Meg and he enjoys her blushes. He’s found ways to raise them but something more is happening here. When she leaves abruptly, he wants to track her down but his broken leg makes pursuit difficult. Now he must find a way to win her over and that takes some time and clever moves

My fellow BWL author, Janet Lane-Walters, invited me to visit her blog today. See Janet’s blog for my answers to the following questions, which I have asked Janet.

Question 1. Welcome Janet. Tell us readers, what were you in your life before you became a writer? Did this influence your writing?

I think I always was an aspiring writer but what I loved as a teen was doing non-fiction papers. Then I became a nurse, trained at a hospital school in Pittsburgh, Pa.  I continued writing non-fiction papers except the teachers said I put in too much about the families, physical descriptions of them and their homes that weren’t necessary to the papers. That must be where fiction began to creep in. I worked as a nurse, got married and had children. During this time I began to write and have persisted to this day. First published in 1968 with a short story.

I continued writing non-fiction papers except the teachers said I put in too much about the families, physical descriptions of them and their homes that weren’t necessary to the papers. That must be where fiction began to creep in. I worked as a nurse, got married and had children. During this time I began to write and have persisted to this day. First published in 1968 with a short story.

2 Are you genre specific or general? Why? I don’t mean genres like romance, mystery, fantasy etc. There are many subgenres of the above.

I am genre general. I’ve tried many forms of romance and also dabbled in cozy romances. The romances fall into medical, paranormal – mostly fantasy but some are alternate world and reincarnation. There may be a bit of mystery thrown in with the romance and sometimes a bit of paranormal creeps in. I also have a fantasy series for Young Adults that contains a lot of suspense. There are a couple of non-fiction books with my name attached. One won an EPIC award as the best of 2003.

3. Did your reading choices have anything to do with your choice of a genre or genres?

Reading has definitely slanted my writing. I read just about anything except horror and preachy inspirationals. Horror creeps me out a lot.

4. What’s your latest release?

4. What’s your latest release?

My latest release – Two double books with one more to come. Seducing the Blakefield Sisters and Seducing the Blakefield brothers. They’re short, spicy romances.

5. What are you working on now?

Right now, I’m working on the fourth of the Opposites In Love series – The cancer-Capricorn Connection and revising a reincarnation novel Past Betrayals; Past Loves. Also trying to update a lot of books for BWL press. I’ve done a number but there are more to go.

6. Where can we find you?

http://janetlanewalters.com/home

https://www.facebook.com/janet.l.walters.3?v=wall&story_fbid=113639528680724

My publisher gave me a regular spot on their website’s author insider blog. I’ll be there the 12th of every month. Check out my first offering about the one blog post I wrote that made a difference.

My publisher gave me a regular spot on their website’s author insider blog. I’ll be there the 12th of every month. Check out my first offering about the one blog post I wrote that made a difference.