Will and I spent most of November in Puerto Vallarta and enjoyed the build-up to Christmas.

All posts by admin

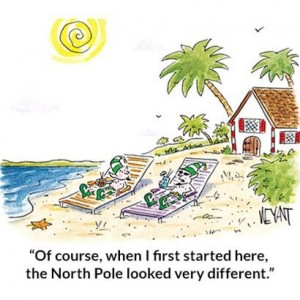

Christmas Climate Change

Christmas Group Therapy

Christmas Elvis

Beatrix Potter’s World

In today’s Books We Love author blog, I write about my visit last spring to Beatrix Potter land in England’s Lake District.

Canadian Battlefields of Northern France

On Remembrance Day this year, I reflected on my trip to the Canadian battlefields of northern France in my post on my publisher’s website. Here is the post, for those who missed it.

Yesterday, November 11, marked the 100th anniversary of the formal end of World War 1. The occasion led me to remember my trip to Europe three years ago with my husband Will and our son Matt. We began our tour of Canada’s battlefields with a stop at the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in northern France.

From the Vimy visitors’ centre, we walked up to monument, past a section of land that has been forested to prevent erosion. A sign told us that the bumpy terrain was caused by mine explosions during the war. German troops planted the mines when they occupied the strategic ridge from 1914-1917. The explosions went off as Allied forces advanced up the hill. Barbed wire fences and “Keep Out” signs warned that unexploded munitions remain buried under the grass.

Our approach led to an impressive sight. Sculpted of Croatian limestone, the Vimy monument features 20 human figures representing peace and the defeat of militarism.

The names of 11,285 Canadians killed in France whose graves are unknown are inscribed on the memorial’s outside wall. Back down the hill, we stopped at the cemetery for the Canadian soldiers who died at Vimy or on neighbouring battlefields.

Student guides conducted a tour of the preserved trenches and tunnels.

Moved by all we’d seen at Vimy, we drove to the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial. Newfoundland didn’t join Canada until 1949 and fought as a separate regiment in WWI.

| Beaumont-Hamel caribou monument |

On July 1 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, the Newfoundlanders left the trenches to storm a ridge occupied by German forces. Most of the soldiers made it less than half way before they were mowed down by German guns and artillery. An Allied explosion set off earlier had warned the Germans of the impending attack. The Newfoundland regiment failed to take the ridge.

| Plaque in Musee Somme 1916, in the town of Albert, France |

Nearby, in Thiepval, we visited the Memorial to the Missing of the Somme, where graves of British Commonwealth and French soldiers represent the joint nature of the 1916 Somme offensive. The British Commonwealth headstones are rectangles made of white stone; the French headstones are grey crosses.

We left France and drove toward Bruges, Belgium, for several days of respite from war. But on the way we stopped at Ypres, the location of several WWI battles that virtually destroyed the city. After the war the city was rebuilt to its former style, attractively we felt.

| Main square in Ypres |

At the Ypres Memorial to the Dead, people were setting up for the weekend’s ceremony to commemorate the first poison gas attack, which took place in Ypres in April 1915. Lights shining on the stone monument’s list of war dead cast an ominous glow.

Lest We Forget

Today, one day after this year’s special Remembrance Day, I write about my visit to Canada’s WWI battlefields in northern France on the BWL Author BlogSpot.

Opening Weekend at Calgary’s New Central Library

-

- The sun came out as we were leaving.

I loved visiting Calgary’s new Central Library today, along with the estimated crowd of 20,000 – 25, 000 people. The building is fabulous. The guided tour helped me appreciate many of the library’s features. I can’t wait to go back, when it’s less crowded and quieter.

New Central Library

I look forward to visiting Calgary’s new Central Library tomorrow. A host of events will take place during the day, with free public transit to downtown from 7:00 am to 7 p.m. I’ll be sure to check out my story in art form featured with 12 other artist books on the 4th floor in the NW Vestibule entrance to the Great Reading Room.

To support this exhibition, there will be a year’s worth of programming the second Tuesday of every month in the BMO Room from 7-8pm beginning January 15, 2019 with Kate Baillies and Weyman Chan. My artist Sylvia Arthur and I will be there on August 13th to talk about our collaborative project.

William Wordsworth’s Beloved Homes

England’s Lake District was a highlight of my trip to Britain last spring. Earlier this month, on my publisher’s author blogspot, I recalled my visits to the homes of poet William Wordsworth. This is what I wrote:

I’ve wanted to visit England’s Lake District since my university days, when I took a course in Romantic Poetry. The Lake Poets, my professor said, turned to nature as a reaction against the country’s industrialization, not unlike the hippies of our time. None was more associated with the bucolic lakes than William Wordsworth, who was born in the region, travelled away for awhile and returned to marry and live the rest of his long life. Last spring I learned why he loved The Lake District so much when I spent a week there.

| A walk near Grasmere – in The Lake District everywhere you look is a picture |

On one of those fine days, my husband and I visited two of Wordsworth’s homes in the village of Grasmere. We arrived early at Dove Cottage, William’s starter house when he married, and got a private tour before a busload of tourists crowded the small rooms. The guide pointed out the poet’s favourite artifacts, which included a cuckoo clock that made William and his sister Dorothy laugh hysterically each time the bird popped out. Life was simpler then.

| Dove Cottage, where we learned that during his lifetime Wordsworth was always referred to by his first name |

| William’s funny cuckoo clock |

| William built a terrace in the garden behind Dove Cottage to get a view of the lake, now obscured by houses and trees. |

William earned some money from poetry and worked as a Distributor of Stamps, but much of his income was inherited from his father and an acquaintance who died young and left the poet money to support his talent. From Dove Cottage, we walked a 40 minute path to Rydal Mount House & Gardens, William’s more upscale home, where he lived from 1813 until his death in 1850. Here he wrote and revised many of his poems and published his most famous one, ‘Daffodils.’ The Wordsworths rented the house until his wife’s death in 1859. Their great great granddaughter later bought the property, opened it to the public in 1970 and still uses it for family gatherings.

| Rydal Mount |

| I liked that the living room looks lived-in |

| Rydal Mount grounds |

Rydal Mount’s huge garden looks much as it did in William’s time. William often said the grounds were more his ‘writing room’ than his office in the house. He was known to recite his poems aloud while revising them and often did this on his solitary walks through the countryside. William was born before the invention of trains and wasn’t rich enough to own a horse and carriage. He thought nothing of walking five hours to the northern Lake District town of Keswick, to visit his friend and fellow Romantic poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Writing, walking, wandering through gardens. What a wonderful lifestyle.

| We were too late in the season for William’s daffodils, but we walked past fields of bluebells. |

![20181103_141329[28692]](http://susancalder.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/20181103_14132928692-e1541285560934-225x300.jpg)

![20181103_120002[28693]](http://susancalder.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/20181103_12000228693-e1541285013215-225x300.jpg)

![20181103_113714[28694]](http://susancalder.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/20181103_11371428694-300x225.jpg)

![20181103_143242[28691]](http://susancalder.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/20181103_14324228691-300x225.jpg)