Today on the BWL website I blog about about my literary tour of Ireland. https://bwlauthors.blogspot.com/

Today on the BWL website I blog about about my literary tour of Ireland. https://bwlauthors.blogspot.com/

Happy Orangeman’s Day — or not.

July 12th is a holiday in Northern Ireland, commemorating the victory of Protestant William of Orange over Britain’s Catholic King James II at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. Ulster Protestants celebrate the day with marching band parades; Catholics escape the noise and traffic snarls to beaches in the southern Republic of Ireland.

A month ago, my husband Will and I took a bus tour through Belfast, Northern Ireland. Union Jack Flags, red, white and blue banners, and posters of Queen Elizabeth II decorated homes and businesses in Protestant neighbourhoods in celebration of her majesty’s recent Jubilee weekend. Our tour guide said people would leave the decorations up another month for Orangeman’s Day. The splashy displays ceased abruptly when we crossed into Catholic neighbourhoods.

During The Troubles in Northern Ireland from the late 1960s to late 1990s, Orangeman’s Day was often marked by riots and violence. Protestants would provoke conflict by marching into Catholic neighbourhoods. During that thirty year ‘irregular war’ that killed more than 3,500 people, I wouldn’t have considered a holiday in Belfast, but I didn’t give it a thought this year. We stayed in the Europa Hotel, which experienced 36 bomb attacks during The Troubles and was called the most bombed hotel in the world. Since then, the renovated hotel has gone high tech with ‘smart’ elevators and window blinds.

Our tour bus stopped at the peace wall that divides the predominantly republican, nationalist, Catholic Falls Road area from the loyalist, unionist, Protestant Shankhill Road area of West Belfast. These peace lines are supposed to be removed by 2023, but they’ve become popular tourist attractions. Former IRA members conduct black taxi tours of the walls, complete with their versions of The Troubles and the current political situation. I found this image an unsettling reminder that the conflict isn’t over.

This was brought home to me even more in Londonderry or Derry, depending on your political view. Ireland’s second largest city is located close to the Irish border and is about 75% Catholic (Belfast is roughly 49% Catholic). A local guide gave us a tour of the Derry walls, built in the 1600s as a defense against Catholic attacks. He said that during The Troubles Catholics, who lived largely across the river, weren’t allowed into the city gates. It’s hard to believe this is recent history.

Since the Catholic and Protestant neighbourhoods rise up from the river banks the city’s political divide is visible. Recently there has been some merging. Our guide said he grew up on the boggy Catholic side, but now lives in Protestant (London)Derry. During The Troubles, he knew people who had never ventured to the opposite side of the river. Since 2011, a pedestrian Peace Bridge has connected the two divides. Some suggest the bridge’ s ‘falling-over’ design reflects the shaky peace. Our guide noted that Brexit has refueled the push for a unified Ireland. He pointed out a section of sidewalk damaged by a car bomb, the first since the 1998 Good Friday Agreement that ended The Troubles.

Peace Bridge, Londonderry/Derry

Last fall I wrote a historical mystery short story and showed the first four pages to a local Writer-in-Residence. The WIR’s main advice was to turn the story into a novel. I had no clue how I’d do this and she didn’t offer suggestions, but I was intrigued by the idea.

Then this spring BWL decided to publish a collection of Canadian Historical Mysteries. They assigned thirteen of their authors to write a novel set in a specific Canadian province or territory. The collection will have twelve books — British Columbia is co-authored and Nunavut/Northwest Territories will be reunited in one of the books. I’m delighted to represent my home province of Alberta.

BWL asked us to provide a working title and novel blurb, which they’ll publish in a free guidebook as advance promotion. This got me mulling ways to expand my short story, which was set in Calgary during the 1918 influenza pandemic and told through the viewpoint of a police detective. The WIR’s other suggestion was to change the protagonist to a character who was present at the victim’s death, to make that aspect of the story more immediate. One of the suspects appealed to me as a point-of-view narrator, but if I let readers enter his thoughts I’d lose him as a suspect. Also, while I like experimenting with male protagonists in short stories, I prefer to write female protagonists for novel-length works. This led to my idea for a new character and protagonist, the sister of that suspect. She will be motivated to solve the crime to know if her brother or someone close to him is guilty of murder.

I plan to keep my detective as a secondary narrator. His investigations and personal story will increase the material. In the short story, he had a romantic interest in a co-worker. For the novel I’ll shift his interest to my heroine to enhance their relationship. She’s married, but her husband has been overseas for four years, fighting in The Great War, and she’s changed during that time. Her feelings for the detective will create lots of conflict for them both.

My other idea is to add a new suspect to this longer story; a man who opposes the war. The victim and my heroine’s brother are injured veterans, who received an early discharge. WWI officially ended November 11, 1918, in the middle of the second and deadliest wave of the influenza pandemic, but most of the Canadian troops didn’t return until the following spring. I’d like to make the war more present in the novel than it was in the short story, from the perspectives of those on the home front.

I’m satisfied these additions and changes will be enough to expand my 4,500 word short story to a 75,000 word novel, the median length of the books in the collection. More importantly, I’m eager to write the larger story to develop these characters and find out what happens to them in the new version.

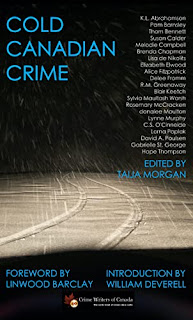

In effect, the short story is my novel outline. I’m sure much will change in the process of writing the book. Even whodunnit and why the person done it and how he or she done it are up for grabs. So if you read the short story, don’t worry about spoilers. After I showed the WIR those first pages, the short story was accepted for publication. It appears in the recently released Cold Canadian Crime Anthology, available on Amazon, Kobo, and other sites.

A new title will be one definite change for the novel. The the short story title “A Deadly Flu” was a wink at my first novel, A Deadly Fall. Two similar novel titles would create confusion.

Here’s the cover for the Canadian Historical Mysteries guidebook, which you will soon be able to download for free to read the twelve novel descriptions.

For updates, check out the BWL Canadian Historical Mysteries Page https://bookswelove.net/authors/canadian-historical-mysteries-collection/

Check out the my publisher’s website for my blog post about BWL’s new Historical Mysteries Collection and the story I plan to contribute. https://bwlauthors.blogspot.com/

Yesterday Cindy DeJager launched her Coffee and Conversation with authors series on YouTube. I’m her first subject. Please listen and Like and Subscribe for free so Cindy can reach her first 100 YouTube subscribers. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ibNmn_2k9DE&feature=youtu.be

This winter Tourism Calgary sent me an email out-of-the-blue. They explained they were considering a bid for the 2026 Bouchercon World Mystery Convention and wanted my help connecting with the Calgary writing community. The bid needed sufficient volunteer support to host this major convention. Tourism Calgary had done an internet search for local mystery writers and my name popped up in various places. They thought the convention could have numerous spinoff benefits for Calgary.

I’d first heard about Bouchercon at Mystery Writers’ INK, a Calgary writing group I belonged to for many years. Members considered it the premiere mystery writing convention in North America. A couple of them attended Bouchercon 2007 in Anchorage, Alaska. They described their experience as a fun mix of learning, book promotion, and travel. Many Bouchercon regulars plan annual holidays around the convention.

I was excited by the email and agreed to meet online with two Tourism Calgary contacts, and later with them and the Bouchercon administrator. I learned that Bouchercon is huge. Typically about 1,800 people attend. The majority are mystery fans, rather than writers. Bouchercon is usually held in the USA, although Toronto, Canada, has hosted three times and the U.K. twice. In London 1990, P.D. James was Guest of Honour. Nottingham England’s Lifetime Achievement Guest of Honour in 1995 was Ruth Rendell (not Robin Hood). Other Guests of Honour through the years have included Sara Paretsky, Ian Rankin, Harlan Coben, Laura Lippman, James Patterson, Michael Connolly, Anne Perry, Karin Slaughter, Anthony Horowitz — enough name dropping.

In October 2017, I attended Bouchercon Toronto. Louise Penny was Canadian Guest of Honour. (Each Boucherson has about a half dozen Guests of various descriptions). I moderated a panel on Noir Mystery Novels to a large audience (scary, both the moderator role and the subject matter). Each convention produces a short story anthology, with the proceeds going to a charity. A highlight for me was my story’s acceptance in Passport to Murder, Bouchercon Anthology 2017. This earned me a seat at the author signing table.

The Bouchercon administrator told us their organization provides a wealth of support and experience for host cities, but, in addition, Calgary would require a strong Local Organizing Committee. I provided Tourism Calgary with names of people and local groups to contact, including BWL. Our publisher, Jude Pittman, was instantly on board and will be part of the committee. Tourism Calgary sent a survey to local writers and organizations and the enthusiastic response exceeded everyone’s expectations. Calgary is called the volunteer capital of Canada for good reason. The Calgary Public Library, Calgary Wordfest, and the University of Calgary expressed interest in playing roles.

Tourism Calgary is now preparing a formal bid to host the convention in 2026. In June the Bouchercon administrator will fly to Calgary to assess the city’s hotel and convention capacity. If it meets the criteria, I’m told Calgary stands a great chance of winning the bid when the Bouchercon board votes this summer.

Since I’ve been with them from the start, Tourism Calgary asked me to chair the Local Organizing Committee. After some angst, I agreed to co-chair with Calgary author Pamela McDowell, my friend for 25 years. Pam and I will be busy, but it will be fun to work together on this big project.

Looks like Calgary mystery writers and readers are in for exciting years ahead. Stay tuned.

Bouchercon 2017 was an opportunity to visit Toronto in the fall

Today on the BWL website I write about Bouchercon World Mystery Convention. https://bwlauthors.blogspot.com/

I’m a believer in plowing through a novel’s first draft without pausing to revise along the way. When I start writing a book, reaching ‘the end’ is a daunting prospect. Since reworking existing material is easier than tackling a blank page, it can become an avoidance tactic. It might also be a waste of time if I discover I have to delete or radically rewrite a scene after I know what the whole story is about. ‘Write and revise later’ worked for my first four books. It didn’t for my current novel-in-progress.

My first problem with the process occurred when a scene I wrote fell flat and I felt a need to revise it before moving forward in the story. This happened again a few scenes down the road. In one case, my point of view detective narrator needed a partner for the scene. I threw in a random police officer, but found he added nothing to the story. I went back and made him a ‘she.’ To my surprise, sparks flew between her and my detective, who is at a crossroads in his life. Their romance has become a subplot in the novel and a key aspect of his personal story arc.

I tell myself that modifying my usual approach and following my instinct to jump in and revise comes from having a few novels under my belt; that I now know earlier in the process what a story needs to avoid more complicated revision later. How’s that for self-justification?

Around the manuscript’s 3/4 point, I realized that a number of scenes in the third quarter would work better if they were set in different locations. This time I stuck with my usual approach since most of the other material would remain the same. Instead of revising the scenes, I made an outline for the changes I plan to make. They will move a critical plot point earlier in the story, but I think the outline can deal with this change. Revising the wayward scenes would have benefits, but I really want to finish the first draft this spring.

Then, a few chapters later, a long scene fell completely flat, when the story should be building to a thrilling climax. I puzzled over what to do and decided I’d taken a wrong turn at the 3/4 mark. I had shifted the story focus to a character who is much talked about but hadn’t made a personal appearance in the novel. I assumed that since my main characters cared deeply about him, readers would too. But I think readers only engage with the characters they meet in the literary flesh. This might be one reason they tend to be less interested than the writer in characters’ backstories.

My solution to this problem will be to go back three chapters, to the point where I veered off track. I’ll revise most of the scenes and cut the 2,000 word flat scene. Ouch. But I need to know what happens in these chapters to figure out my characters’ paths to the climax and denouement.

Each novel has its own journey. This work-in-progress has gone in directions I didn’t expect, in terms of character development, subject matter, and writing process. I’ve found it a challenge to adapt, without steering off course.

My turn today on the BWL Blogspot. https://bwlauthors.blogspot.com/ I discuss ‘When Your Novel Takes a Wrong Turn.’

One thing I like about writing short stories is the chance to explore genres and characters different from those of my novels. Last fall I completed my first work of historical fiction, a 4,500-word story set during the 1918 influenza pandemic. A Deadly Flu is also my first short whodunit and my first police procedural. I’ve featured detectives in secondary roles before, but not as story protagonists.

My idea for A Deadly Flu took root almost two years ago, when the COVID-19 pandemic revived my interest in that earlier virus, which was formerly and inaccurately called the Spanish flu. I first heard about the 1918 pandemic on an episode of the 1970s television show, Upstairs Downstairs, when the young wife of the wealthy Bellamy family’s son developed a fever and died the same day.

During the summer of 2020, I read books and articles about the 1918 pandemic and was struck by its relevance a hundred years later. The prime advice in both pandemics was the same: wash your hands, social distance and avoid crowds. The 1918 Pandemic’s second and mostly deadly wave struck my home city of Calgary from October to December 1918. Business, churches and bars closed. People wore masks and lived in fear.

Around this time, I was mulling ideas for my fourth mystery novel, to be set during our current pandemic, and wondered if the 1918 flu might provide a parallel backstory. I developed the idea of a pharmacist who murders her lover by pouring a medicine that mimicked the 1918 flu’s symptoms into his whisky. When he died, the medical profession’s tunnel vision assumed this was another influenza death.

I began writing the backstory as a suspense from the killer’s viewpoint and enjoyed researching Calgary neighbourhoods of the time, along with its streetcar system, fashion, and particulars of the city-wide lockdown. But by the end of the draft, I realized the events that happened over a hundred years ago wouldn’t add enough interest to the contemporary mystery I had in mind. I set the backstory aside and plunged into the current novel.

Nov 11, 1918 – Calgary WWI Victory parade

Then the Crime Writers of Canada put out a call for submissions for its 40th anniversary anthology. Stories had to be set in Canada, feature cold in some way, and be under 5,000 words. I hauled out the backstory and set it during a Calgary cold wave in December 1918, with a detective, rather than a villain, protagonist. A benefit of writing a detective from the early twentieth century is that I didn’t have to know about DNA, data bases, and other modern police gadgetry. Since I only had a short space to establish reader connection with him, I gave him a wound–his wife had died a year earlier in childbirth–and developed a romantic subplot.

I wrote the story, sent it off, and was thrilled last month to learn A Deadly Flu will be included in the Cold Canadian Crime Anthology, to be released this May. Meanwhile I’ve been working on my novel-in-progress. Inspired by my historical detective, for the first time I’m including the viewpoints of two detectives in addition to my insurance adjuster sleuth. I foresee much research into modern police work. One day soon, I’d like to write a historical novel and, perhaps, develop A Deadly Flu into a novella, a genre I haven’t tried. That’s another thing I like about writing short stories—they can be stepping stones to future books.