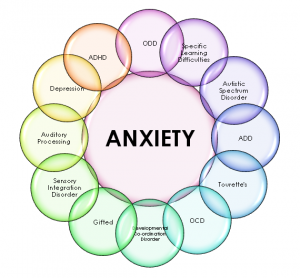

I wrap up February Psychology Month with a look at evolution and Anxiety/Depression: two sides of the same coin?

In the 1950s and 60s, anxiety was the most commonly diagnosed mood disorder in North America. People talked of the Age of Anxiety; The Rolling Stones sang about Mother’s Little Helper, a reference to a tranquilizer commonly prescribed to housewives.

Starting in the 1970s, anxiety became eclipsed by depression. Today, prescriptions for anxiety are dwarfed by antidepressants, the most prescribed medication of our times.

Why this change? ask Allan V. Horwitz and Jerome Wakefield, authors of All We Have to Fear: Psychiatry’s Transformation of Natural Anxieties into Mental Disorders.

And, furthermore, where is the line between natural anxiety and a disorder?

Their answers to this last question come from an evolutionary perspective. In the primitive world, where dangers were ever-present, anxious vigilance made sense. Fear of strangers, status fears like making a public fool of oneself, fears of snakes, rodents and heights increased your chances of evading disaster. Better to over-react every time, than to relax once and die. Those anxious genes of survivors were passed on to their modern descendants.

Their answers to this last question come from an evolutionary perspective. In the primitive world, where dangers were ever-present, anxious vigilance made sense. Fear of strangers, status fears like making a public fool of oneself, fears of snakes, rodents and heights increased your chances of evading disaster. Better to over-react every time, than to relax once and die. Those anxious genes of survivors were passed on to their modern descendants.

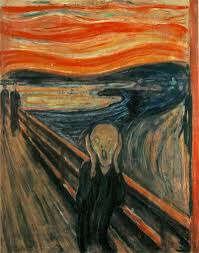

In today’s world, strangers rarely present a threat; if one group of friends hate you, you can find another group; city dwellers are unlikely to encounter snakes and in northern climates snakes usually aren’t poisonous. Yet such fears are bred into us and can seriously impact our lives. Fear of flying is a common anxiety because it combines several archetypal fears – enclosed spaces, heights, loss of control. It wasn’t clear to me at what point the authors felt these fears should be treated by medicine or therapy, but they got across their view that these anxieties are rooted in human nature. It made me feel less odd about freaking at the sight of a mouse.

The authors’ first question reminded me of a movie — I believe it was Starting Over (1979) — where a person had a panic attack at a large gathering of women and a character asked, “Does anyone have a valium?” Every woman reached for her purse. Valium was that decade’s most prescribed anti-anxiety medication, although by 1979 anxiety was already losing ground to depression.

was Starting Over (1979) — where a person had a panic attack at a large gathering of women and a character asked, “Does anyone have a valium?” Every woman reached for her purse. Valium was that decade’s most prescribed anti-anxiety medication, although by 1979 anxiety was already losing ground to depression.

People didn’t change in the 70s and 80s, Horwitz and Wakefield say, becoming less anxious and more depressed. Anxiety and depression have many overlapping symptoms. Sufferers often shift between symptoms of each that could arguably be treated as a single illness. What changed was the diagnosis. This happened for a convergence of reasons.

The anti-psychiatry movement of the 1960s and 70s heightened the psychiatric profession’s inferiority complex (my words) relative to other medical specialties. Psychiatrists wanted to be viewed as scientific and, well, medical. They accomplished this by changing the focus of the 1979 DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual) away from unproven causes to symptoms, which could be clearly specified.

Major depression has always been recognized as a serious illness, one that might require hospitalization like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Around this time, insurance companies were increasingly covering drugs that patients used to pay for on their own. The insurers wanted proof that applicants required treatment for medical reasons. The DSM III defined depression as a mental disorder, with simple qualifications – two weeks duration and general symptoms that might be mild, moderate or severe. The manual eliminated general anxiety as a disorder, requiring the anxiety be specific (ie. Social Phobia, Fear of Flying) and that it continue for long periods of time, sometimes years. Diagnoses for general malaise quickly shifted to depression so patients could receive insurance payments.

Major depression has always been recognized as a serious illness, one that might require hospitalization like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Around this time, insurance companies were increasingly covering drugs that patients used to pay for on their own. The insurers wanted proof that applicants required treatment for medical reasons. The DSM III defined depression as a mental disorder, with simple qualifications – two weeks duration and general symptoms that might be mild, moderate or severe. The manual eliminated general anxiety as a disorder, requiring the anxiety be specific (ie. Social Phobia, Fear of Flying) and that it continue for long periods of time, sometimes years. Diagnoses for general malaise quickly shifted to depression so patients could receive insurance payments.

In addition, by the late 1970s, anti-anxiety medications were getting a bad rap, due to claims of their addictive qualities. In the 80s, when the giant pharmaceutical companies developed Prozac and other new types of drugs, they marketed them as antidepressants, although they might as accurately have marketed them for anxiety. In fact, some of those medications have since been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for specific anxiety disorders. In 1999 the FDA approved Paxil for Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) and Zoloft for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Horwitz and Wakefield predict more approvals will follow, breathing new life — and profits — into the tired antidepressants.

- Huffington Post Poll

They also predict a shift in diagnoses from depression back to anxiety. They note that the same sort of attacks that happened to the anti-anxiety medications in the 1970s are now happening to the antidepressants, “with questions about their effectiveness, side effects, potential addictiveness and safety.” In addition, the patents for the antidepressants will soon start running out, resulting in lower profits for the pharmaceutical companies. This should prompt them to develop newer drugs to treat newly-defined disorders.

The authors add that, “The diagnosis of depression is no longer as useful to psychiatry as it was over the past quarter-century. The profession’s scientific credibility is now far greater than it was in the 1970s, its diagnostic system is generally regarded as reliable, and its biological models are widely accepted.” As a result, they expect psychiatrists to be more willing to diagnose anxiety. It will be treated by the pharmaceuticals’ new type of medication marketed to treat anxiety, now acceptable to insurers as a genuine disorder.

I would add that anxiety is becoming more socially acceptable. It used to seen as a women’s problem; now men are admitting to having it.

![celebrating-25-years-400[1]](http://susancalder.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/celebrating-25-years-4001-300x251.jpg)