Many thanks to journalist Eric Volmers for this feature on To Catch a Fox in today’s Calgary Herald newspaper.

Many thanks to journalist Eric Volmers for this feature on To Catch a Fox in today’s Calgary Herald newspaper.

One week from today, Tuesday, March 26h, I’ll be launching To Catch a Fox at Owl’s Nest Bookstore. My presentation will feature slides from my two holidays in Southern California to research settings for the novel. Everyone welcome!

![celebrating-25-years-400[1]](http://susancalder.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/celebrating-25-years-4001-300x251.jpg)

In my interview with Randy Luckie, we talk about a wide range of writing subjects including my new novel, my mystery series, short stories, getting published, Stephen King, and murder by bee sting.

As an aside to the interview, I have stalked Stephen King’s home in Bangor, Maine, a couple of times. I grew up in Montreal and every summer my family drove through Maine to my grandparents’ home in New Brunswick, Canada. Our route went through Bangor, where we sometimes spent the night. When I was older, I continued to make the trek with my husband every couple of years.

When we learned that Stephen King lived in Bangor, on one of those drives we stopped at a local bookstore to ask where the author lived. The store owner didn’t hesitate to give us directions to the house. I believe the owner talked about seeing King often at his sons’ baseball games.

During subsequent trips through Maine to New Brunswick, we made at least one more detour to King’s house. I found it suitably ominous-looking for the master of horror.

I was also impressed that one of North America’s most successful authors made his home in down-home Bangor.

For those who missed my regular post on my publisher’s website last month, here it is:

Last fall a writer friend asked me, “Is it worthwhile having a book launch?”

I immediately answered, “Yes.” I’d hosted launches for my first two novels and planned to have one for my third release, To Catch a Fox. But my friend’s question prompted me to ask myself: what is the value of a bookstore launch in this age of e-books and online sales?

So here are my Top Five reasons for hosting a book launch.

1. It is a gracious way to tell people about my new novel. Instead of sending an email notice and link to a sales site, I am inviting them to a launch party. Some will feel pleased that I included them in my special event. Most won’t come to the launch, but they’ll have enough details to buy the book online or at their favourite book store, without my asking them to do it.

I’d suggest inviting everyone in your circle of acquaintanceship. For my first launch, I asked people in my gym class I’d barely spoken to before.

“You’re a writer?” some said, intrigued.

It started conversations and closer connections because I’d shared something personal about myself.

|

| For my last book launch I designed an invitation postcard, but economized by printing invitations at my library |

2. If you invite people, many will come. My first book launch drew close to 100 people, my second about 85. Both times, they packed the bookstore and a fair number bought copies of the book. Admittedly my two novels were long awaited releases. I’d worked on the first book for years before finishing it and finding a publisher; the second wasn’t published until 6 years later. Now with only a two year gap between my second and third launches, I don’t expect friends and relatives to feel as strong a need to come out and support me. But I’m hoping that newer friends and–dare I say it–fans will make up for some attrition.

| Don’t forget the food and drink for your guests |

|

The crowd gathers |

3. Local media is more inclined to focus on an event the public can attend than on a book release. The entertainment editor of my Calgary Herald newspaper profiles an author most weeks. When he chooses a local writer, it’s almost always someone with an upcoming book launch or major reading. He schedules the piece for the week leading up to the event. Other local print media, radio and television might be similarly event-focused. It’s hard to get your books into any media, but a launch gives you a better chance. Independent bookstores also focus on events to draw customers and are likely to display your books and the launch announcement in their store windows during the week leading up to the launch.

4. You might make your newspaper’s local bestsellers’ list. The Calgary Herald, my daily newspaper, publishes a local bestsellers’ list in its Saturday edition. The tiny print at the bottom states the list is complied by information provided by the Calgary’s 2-3 independent book stores. Sales at these stores are so low that any book that sells decently at a launch is almost guaranteed a spot on the list. Many newspaper readers look at the list for ideas of what to read. I know that other city newspapers have this feature. It’s worth checking out.

|

| Calgary Herald Bestserllers’ List 2 weeks after my last launch & profile the weekend before the launch |

5. And lastly, a launch is a celebration. You’ve worked hard on this book and deserve a party with family, friends and your devoted readers. Many venues are free or inexpensive. Food and drink might set you back $50-75, but aren’t you, your book and your supporters worth it!

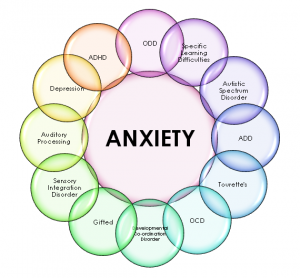

I wrap up February Psychology Month with a look at evolution and Anxiety/Depression: two sides of the same coin?

In the 1950s and 60s, anxiety was the most commonly diagnosed mood disorder in North America. People talked of the Age of Anxiety; The Rolling Stones sang about Mother’s Little Helper, a reference to a tranquilizer commonly prescribed to housewives.

Starting in the 1970s, anxiety became eclipsed by depression. Today, prescriptions for anxiety are dwarfed by antidepressants, the most prescribed medication of our times.

Why this change? ask Allan V. Horwitz and Jerome Wakefield, authors of All We Have to Fear: Psychiatry’s Transformation of Natural Anxieties into Mental Disorders.

And, furthermore, where is the line between natural anxiety and a disorder?

Their answers to this last question come from an evolutionary perspective. In the primitive world, where dangers were ever-present, anxious vigilance made sense. Fear of strangers, status fears like making a public fool of oneself, fears of snakes, rodents and heights increased your chances of evading disaster. Better to over-react every time, than to relax once and die. Those anxious genes of survivors were passed on to their modern descendants.

Their answers to this last question come from an evolutionary perspective. In the primitive world, where dangers were ever-present, anxious vigilance made sense. Fear of strangers, status fears like making a public fool of oneself, fears of snakes, rodents and heights increased your chances of evading disaster. Better to over-react every time, than to relax once and die. Those anxious genes of survivors were passed on to their modern descendants.

In today’s world, strangers rarely present a threat; if one group of friends hate you, you can find another group; city dwellers are unlikely to encounter snakes and in northern climates snakes usually aren’t poisonous. Yet such fears are bred into us and can seriously impact our lives. Fear of flying is a common anxiety because it combines several archetypal fears – enclosed spaces, heights, loss of control. It wasn’t clear to me at what point the authors felt these fears should be treated by medicine or therapy, but they got across their view that these anxieties are rooted in human nature. It made me feel less odd about freaking at the sight of a mouse.

The authors’ first question reminded me of a movie — I believe it was Starting Over (1979) — where a person had a panic attack at a large gathering of women and a character asked, “Does anyone have a valium?” Every woman reached for her purse. Valium was that decade’s most prescribed anti-anxiety medication, although by 1979 anxiety was already losing ground to depression.

was Starting Over (1979) — where a person had a panic attack at a large gathering of women and a character asked, “Does anyone have a valium?” Every woman reached for her purse. Valium was that decade’s most prescribed anti-anxiety medication, although by 1979 anxiety was already losing ground to depression.

People didn’t change in the 70s and 80s, Horwitz and Wakefield say, becoming less anxious and more depressed. Anxiety and depression have many overlapping symptoms. Sufferers often shift between symptoms of each that could arguably be treated as a single illness. What changed was the diagnosis. This happened for a convergence of reasons.

The anti-psychiatry movement of the 1960s and 70s heightened the psychiatric profession’s inferiority complex (my words) relative to other medical specialties. Psychiatrists wanted to be viewed as scientific and, well, medical. They accomplished this by changing the focus of the 1979 DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual) away from unproven causes to symptoms, which could be clearly specified.

Major depression has always been recognized as a serious illness, one that might require hospitalization like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Around this time, insurance companies were increasingly covering drugs that patients used to pay for on their own. The insurers wanted proof that applicants required treatment for medical reasons. The DSM III defined depression as a mental disorder, with simple qualifications – two weeks duration and general symptoms that might be mild, moderate or severe. The manual eliminated general anxiety as a disorder, requiring the anxiety be specific (ie. Social Phobia, Fear of Flying) and that it continue for long periods of time, sometimes years. Diagnoses for general malaise quickly shifted to depression so patients could receive insurance payments.

Major depression has always been recognized as a serious illness, one that might require hospitalization like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Around this time, insurance companies were increasingly covering drugs that patients used to pay for on their own. The insurers wanted proof that applicants required treatment for medical reasons. The DSM III defined depression as a mental disorder, with simple qualifications – two weeks duration and general symptoms that might be mild, moderate or severe. The manual eliminated general anxiety as a disorder, requiring the anxiety be specific (ie. Social Phobia, Fear of Flying) and that it continue for long periods of time, sometimes years. Diagnoses for general malaise quickly shifted to depression so patients could receive insurance payments.

In addition, by the late 1970s, anti-anxiety medications were getting a bad rap, due to claims of their addictive qualities. In the 80s, when the giant pharmaceutical companies developed Prozac and other new types of drugs, they marketed them as antidepressants, although they might as accurately have marketed them for anxiety. In fact, some of those medications have since been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for specific anxiety disorders. In 1999 the FDA approved Paxil for Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) and Zoloft for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Horwitz and Wakefield predict more approvals will follow, breathing new life — and profits — into the tired antidepressants.

They also predict a shift in diagnoses from depression back to anxiety. They note that the same sort of attacks that happened to the anti-anxiety medications in the 1970s are now happening to the antidepressants, “with questions about their effectiveness, side effects, potential addictiveness and safety.” In addition, the patents for the antidepressants will soon start running out, resulting in lower profits for the pharmaceutical companies. This should prompt them to develop newer drugs to treat newly-defined disorders.

The authors add that, “The diagnosis of depression is no longer as useful to psychiatry as it was over the past quarter-century. The profession’s scientific credibility is now far greater than it was in the 1970s, its diagnostic system is generally regarded as reliable, and its biological models are widely accepted.” As a result, they expect psychiatrists to be more willing to diagnose anxiety. It will be treated by the pharmaceuticals’ new type of medication marketed to treat anxiety, now acceptable to insurers as a genuine disorder.

I would add that anxiety is becoming more socially acceptable. It used to seen as a women’s problem; now men are admitting to having it.

One month to go until my book launch for To Catch a Fox.

Four weeks exactly until the date — March 26th.

It’s starting to feel real.

Hope to see you there!

My re-posts about modern pschology and psychiatry continues with The Noonday Demon: an Atlas of Depression by Andrew Solomon. I chose this book because a couple of other books I read mentioned it, with praise.

Demon differs from those other books for several reasons. The author, Solomon, is a writer, not a medical expert. While the experts dealt with mental illness, in general, Solomon focusses on depression, from which he has suffered on and off for seven years (as of 2001, the year of the book’s publication). Solomon did extensive research to write the book, as evidenced by the 100 pages of footnotes and bibliography at the end. Demon is part memoir, part medical information, and part life stories of depression sufferers, many of whom contacted Solomon after an article he wrote about his depression was published in The New Yorker in 1998.

Solomon states up front that he disagrees with the current fashion of opposing medication treatment for depession because his father had a lifelong career in the pharmaceutical industry. As a result, Solomon can view the pharmaceuticals as both capitalist and compassionate, with a genuine desire to cure.

Given the vast numbers of antidepressant prescriptions issued today, as in 2001, I don’t know if I’d call an anti-medication view fashionable. Solomon’s pro-meds view comes out through the book when he criticises doctors and patients who favour going off medication once the person feels well, with relapse as a frequent result.

Solomon, himself, suffered his first breakdown when he was 31, following his mother’s death. Already in psychoanalysis, he sought treatment with medication, recovered, broke down a second time, recovered, and suffered a mini-breakdown before completing the book a year later. As a result, his descriptions of his own experience are detailed and fresh. At the time of writing, he was taking about 12 pills a day, some for side effects of his antidepressant and anxiety meds, and expected to continue on a cocktail of medication for life. He accepts the genetic view of mental illness and all his life story cases portray it as a lifelong disease. This would be my main quibble with the book: there is no sense that someone might recover from this demon state until the distant day some major physical treatment is found.

When The Noonday Demon was published, Solomon was 38 years old. He wrote in the book that he was fine with popping pills for life even though he knew they wouldn’t completely do the trick. It beat the alternative of more frequent and severe breakdowns. He’s now 52, and doing well, from my brief Google search. He’s married, with kids, still writes articles and books and is a professor of clinical psychology at Columbia University. I’d like to know if he’s still taking multiple medications and still relapsing regularly into depression and, if so, is he still okay with this after sixteen years?

The Noonday Demon is a big book, large in scope and information. The medical details are as sound as any I’ve read written by practicing psychiatrists and psychologists; Solomon’s opinions seem as valid as any expert’s, partly because there is no final word on mental illness. Solomon provides many extras the other experts don’t go near. He travelled far and wide to research alternative treatments and try them personally. An exorcism in Africa involved him hugging a ram, the two of them buried under layers of covers, before the ram was sacrificed, its blood drenched over Solomon’s body.

The Noonday Demon is a big book, large in scope and information. The medical details are as sound as any I’ve read written by practicing psychiatrists and psychologists; Solomon’s opinions seem as valid as any expert’s, partly because there is no final word on mental illness. Solomon provides many extras the other experts don’t go near. He travelled far and wide to research alternative treatments and try them personally. An exorcism in Africa involved him hugging a ram, the two of them buried under layers of covers, before the ram was sacrificed, its blood drenched over Solomon’s body.

Solomon was open enough to find merit in most of these treatments, however unusual, although he didn’t suggest that any could compete with medication, ideally supplemented with psychoanalsis. His view of his fellow sufferers in the case histories is sympathetic. I was surprised, though, that after those hours of hugging, he didn’t show more sympathy toward the poor ram that was sacrificed to exorcise Solomon’s demons.

For February, Canada’s Psychology Month, I continue re-visiting my blog post reviews of popular psychology books. Here’s the second re-post:

For February, Canada’s Psychology Month, I continue re-visiting my blog post reviews of popular psychology books. Here’s the second re-post:

When Panic Attacks: the new, drug-free anxiety therapy that can change your life by David D. Burns, M.D.

I picked up this book because some 25 years ago I read Dr. Burns’ earlier bestseller, Feeling Good: the new mood therapy, for a psychology course and found its cognitive therapy approach enlightening. Everyone, I thought, could use a dose of cognitive therapy. In fact, the so-called normal might benefit as much the mentally ill.

When Panic Attacks is a self-help book for people with disabling anxiety. Dr. Burns includes charts as well as space for writing answers to his questions posed along the way. He insists you can’t simply read what he says to get results; you need to be active in your therapy process, with pen in hand. I confess I didn’t write down anything. Mainly, I tried to relate the material to my most anxious, irrational moments, such as my panic when I see a mouse.

Dr. Burns takes a strong stand against the two pillars of modern psychiatry, medication and psychoanlysis. He calls them, generally, useless for anxiety and depression. I get the sense he never prescribes pills. Instead, he makes his patients work on their fears through daily mood logs and applying his 40 ways to defeat your anxiety, until one of those ways works.

His case studies make the process sound easy, but it probably is a lot of work — and scary. His 40 methods include Exposure Therapy, which involves flooding yourself with the object of fear. For me, this would involve bombarding myself with images of mice and rats or real ones. I’d rather take a pill. In addition, my rodent phobia doesn’t affect me enough to truly want to change. During the summer, I still outside on my patio, even though a mouse who lives in the brick wall is likely to scurry by.

Dr. Burns says that a problem with most methods of therapy is that they assume people want to change. In reality, we like the familiar and don’t want to confront our demons and darkest fears.

Anxieties, bad habits and addictions are also rewarding. He often asks his patients, “If you could push a magic button and make all your anxiety, depression or anger disappear right now, would you push that button?” A surprising number of people hesitate.

It seems bizarre, until you realize there are benefits to neurotic fears. He cites an example of a convenience store owner who developed post-traumatic stress disorder after being robbed and beaten at gunpoint. While working on one of Dr. Burns’ charts, the patient came to see that he didn’t want let go of his anger at the perpetrator. The robber deserved it. Anger allowed the patient to feel morally superior. He found satisfaction in being a victim. He believed hanging onto the anger might make him more vigilant against future attacks. All of these thoughts contributed to his continuing PTSD, which he decided, in the end, wasn’t worth these

Author Helen Henderson features To Catch a Fox on her blog titled Journey to the Stars and Worlds of Imagination. While my novel isn’t as fantastical as Helen’s writing, my primary setting for To Catch a Fox is a locale I imagined somewhere in southern California. I had a lot of fun creating my cult-like retreat.