Today is the second installment of my blog post about my five day drive last week from Ottawa to Calgary. I’ve done this route four times before. COVID-19 made it different.

Today is the second installment of my blog post about my five day drive last week from Ottawa to Calgary. I’ve done this route four times before. COVID-19 made it different.

Easter morning, my husband Will and I picked up our breakfast at the motel reception desk. The generous bags included oranges, bagels and muffins, and granola bars that we set aside for later. A package of Easter eggs added a tasty dessert.

We hit the road for day #2 of our drive from Ottawa to Calgary. This is the fourth time we’ve done this trip and we consider this stretch from Sault Ste. Marie to Thunder Bay the most potentially treacherous. The two lane highway winds, rises and falls around Lake Superior. Weather can be harsh and unpredictable. On our eastbound trip in November, we ran into a snowstorm, which made the driving scary for two hours. It didn’t help to see trucks flipped over beside the road. On this return trip, we met fewer trucks than usual and didn’t see any overturned.

Today, the road was clear, the sky a mix of sun and cloud that enhanced the changing views. Lake Superior was still partly frozen. Chunks of snow perched on rocks that jutted from the water. I saw paintings in every direction. Plaques along the road call this section The Group of Seven Highway.

Will and I have two must-stops on the route. The first is the Winnie-the-Pooh park in the railway town of White River. Displays tell how an army captain, en route to Europe in 1914, bought a bear cub from a local hunter and named the cub Winnie after his home city, Winnipeg. He brought the bear with him overseas to England. When he left to fight in France, he donated the cub to the London Zoo. Winnie became popular with zoo visitors, including author A. A. Milne’s son, Christopher Robin, who named his teddy bear after Winnie. This rest is Winnie-the-Pooh history. It’s safe to say that none of this story could happen in today’s more protective age.

Will and I would have eaten our lunch in Winnie’s park, if it wasn’t cold and the picnic tables weren’t snow covered. Instead, we drove into the resort town of Marathon for a car picnic at the beach. We discovered the playground and beach were closed due to COVID-19, but we could still park for a glimpse of the water.

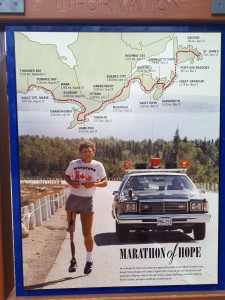

Our second must-stop is the Terry Fox Memorial in Thunder Bay. The monument is located a few miles past the spot where Terry Fox was forced to give up his run across Canada when his cancer returned and spread. He died less than a year later. His memorial is set on a hill with a superb view of Lake Superior. The site is free to visit and a short stop on a long drive. I’d only skip it if I were in a rush, or caught in driving rain or snow, or if it was closed for a pandemic. As Will and I approached the turnoff, we expected to find a barrier at the road entrance, like we’d seen at most of the tourist sites and rest areas we’d passed earlier in the day.

To our surprise, the road curving up the hill was open. The visitor’s centre was closed, of course, but several small groups of people gathered around the monument, respectfully keeping their distance from each other. When Will and I studied the display map of Terry’s Marathon of Hope, we realized that today, April 12, 2020, was the fortieth anniversary of the start of Terry’s run. On April 12, 1980, in St. John’s, NFLD, he dipped his foot in the Atlantic Ocean and began his journey west. It ended Sept 1.

I’m especially glad the monument was open during this pandemic because we need Terry’s message of hope. Let’s hope that by Sept 1, 2020, larger groups will be able to gather at the memorial to celebrate Terry Fox’s courage and inspiration.

On Easter weekend, my husband Will and I set out from Ottawa to drive home to Calgary. We’d spent the winter in Ottawa helping our son Dan through chemotherapy and delayed our trip as long as we comfortably could. Our stay was prolonged by our other son Matt’s return to Ottawa from Mexico. Matt needed us to bring him groceries during his two week isolation. Will and I handled the grocery shopping for three households, Dan’s, Matt’s and our own in a rented apartment. When Matt was released, he joined us in the apartment for a few days together. Thursday, we all enjoyed a farewell turkey dinner at Dan’s house. On Good Friday, Will, Matt and I walked to the trendy Glebe neighbourhood of Ottawa to buy our favourite bagels. In the afternoon, we packed the car and played Canasta (Matt won). Saturday. Will and I hit the road, leaving Matt behind in the apartment to be with Dan for his last treatment.

Traffic on the highway was light, as it had been in Ottawa since the COVID-19 restrictions began and people started working from home. I realized this was one of my few trips to the countryside since we’d arrived in Ottawa on Nov 5, 2019. Our last country excursion was to a maple sugar shack in the Gatineau. We went in early March, the first week of the sugar season, and were glad we did it while we could. This was one of our many ‘glad we went before it closed’ conversations during our last weeks in Ottawa.

Activity on the road picked up at our first stop, Petawawa, with people out for their Easter shopping. We passed a lineup outside the local grocery store, stopped at Tim Hortons for our morning break and were thrilled to find they’d kept one washroom open for customers. The other two were barred off for COVID. At the counter, the clerk said, of course they accepted cash for payment. The stores I’d been to in Ottawa lately had only taken debit or credit cars. I opened my wallet in Tims. My fingers stumbled on the clasp as I momentarily forgot how to pay with cash. When I handed the clerk my toonie, our hands touched, another odd experience these days. While the countryside has geared up for COVID-19, residents might feel less threatened than they do in the bigger cities with their larger illness counts.

After our next stop for gas and a washroom break, we looked for a spot to eat lunch. We’d made turkey sandwiches from our leftover meal and brought snacks to use on the trip. Sudbury’s ring road winds along an escarpment beside the city. We stopped at a lookout and ate in the car, since it was around zero degrees and windy outside. We both reflected on our first trips to Sudbury, in the 70s, when the devastation from the mining activity had reminded me of the surface of the moon. Now, trees make the city liveable.

From Sudbury, we drove to our first night’s lodging in Sault Ste Marie. Sunshine made the landscape along the way pretty. Waterways, rivers and lakes, still partly covered in ice. We’d reserved a motel near the waterfront. Only a couple of cars were there when we arrived. We planned to stay at the Choice hotel chain at each stop on our trip and learned their current policy is to not touch rooms for several days after guests leave, during the time any COVID germs might linger on surfaces. They also don’t clean rooms each day for multiple stays and, instead of their usual hot buffet breakfast, provide a bag of cold breakfast food.

Since we’d arrived early and it was ten degrees and sunny, albeit windy, we walked along the waterfront park, looking for the bust of Roberta Bondar, Canada’s first female astronaut, which we’d seen on our cross country drive many years ago. After posing with Roberta, we picked up a takeout dinner of ribs from Montana’s and brought it back to our room to eat, watching ships cruise down the river between Canada and the US, our mutual border now closed.

Another glad – to have day one, with our longest driving time, under our belts. Four days to go. I’ll report on day two tomorrow.

I was on the road when my monthly blog post on my publisher’s website went live and missed posting this link. I write about how my choir manages to connect during this time of social distancing. (I had to scroll up to see the post)

![Shout-sister[1]](http://susancalder.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Shout-sister1-300x199.jpg)

In 2009 my husband Will and I spent a month in Italy. I hadn’t been to Europe in fourteen years

and was eager to return to its history and culture, but a little anxious about the adventure. Shortly before we were due to leave, the swine flu hit Mexico and the United States. Unlike most flus, including the current Coronavirus (COVID-19), the swine flu (H1N1) didn’t largely kill the elderly and sick. A strain of the 1918 Spanish influenza virus, many healthy, younger people succumbed to H1N1, which quickly spread to Europe. People talked of a worldwide pandemic. And here we were setting out on a plane into this risky situation. I thought of cancelling the trip. But, out of my anxiety came an idea for a short story. A man, grieving the death of his wife, travels through Italy, worried about catching the swine flu. I’d call the story “Pandemic.”

|

| 2009 H1N1 (Swine flu) Pandemic – laboratory confirmed cases and deaths |

In the Rome airport, I noticed several people wearing surgical masks. This struck me as unusual, but now would be common for travel at any time. When I later wrote the story, I included this detail along with others I wrote in a journal I carried through Rome, Venice, Tuscany and Sorrento. Will and I rented weekly apartments in these locations, as did Tony, my story protagonist. I took photos and made notes about our residences, which were part of the story landscape along with the tourist attractions that Tony, Will and I visited.. “Pandemic’s” first turning point occurs when Tony is impressed by Bernini’s sculptures in the Galleria Borghese Museum in Rome. Tony thinks, as I did, how did Bernini make a pinch of skin on a marble thigh look soft and real?

Aside from occasional sightings of surgical masks, I forgot about the swine flu while absorbing Italy’s museums, eating pizza and drinking wine in cafes, exploring ancient sites and warrens of medieval streets. After our trip, The World Health Organization declared H1N1/09 a Pandemic. It was tragic for the people who died. They were fewer in number than those who die annually from a seasonal flu, which is the case so far with COVID-19.

At home, I returned to my novel-in-progress, but Tony’s story kept churning through mind. Eventually, I sat down and wrote “Pandemic,” my first work of fiction set in another country. Aided by my photos and journal notes, I found setting descriptions easier to write than I had in my stories set in Canada. A scene of Tony getting acquainted with two sisters while climbing the Leaning Tower of Pisa felt fresher than my earlier scenes of people meeting in ordinary, North American restaurants. I’ve sometimes thought of “Pandemic” as part story, part travelogue.

|

| In “Pandemic,” Tony and the sisters take comical photos of each other ‘holding up’ the Leaning Tower of Pisa |

“Pandemic” isn’t published yet. At almost 12,000 words, it’s too long for most short story markets and too short for a novella, much less a novel. I’ve broken “Pandemic” down into four standalone stories, set in the different Italian locations. The Venice standalone is titled “Gondolier Groupies;” Tuscany is “La Brezza.” Still no luck with publication. Now, COVID-19 has prompted me to dust off “Pandemic” and revise the whole story again.

I’m finding it interesting to work on a story that aligns with the zeitgeist. The prevailing social mood infuses Tony’s actions and the story descriptions. I’d have thought that immersing myself in the fictional world of a pandemic similar to COVID-19 might make me anxious about our present situation. Instead, it’s a release from worries and the constant talk of disaster, and this is one reason writers write.

|

| In Venice, Tony embarks on an ill-fated adventure with two young women and a pair of gondoliers |

The Coronavirus (COVID-19) got me thinking about my short story, “Pandemic.” I wrote the 12,000 word story 10 years ago, but it was never published. COVID-19 has inspired me to revise “Pandemic.” I find the process helps me put our current crisis into perspective. I write about this in today’s BWL author blog.

![Worldwide-distribution-of-swine-flu-Pandemic-H1N1-2009-Map-reproduced-with-permission[1]](http://susancalder.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Worldwide-distribution-of-swine-flu-Pandemic-H1N1-2009-Map-reproduced-with-permission1-300x171.png)

Earlier this month, I enjoyed Winterlude in Ottawa. Here’s the blog post I wrote for my publisher’s website.

I Embrace Winter – Sort Of

This winter, I’ve had the opportunity to attend Winterlude in Ottawa, Canada, the seventh coldest capital city in the world, according to WorldAtlas. Rather than huddle indoors, Ottawa region residents embrace the season each year with a festival spanning three weekends in early February. The focal point is the world’s largest skating rink, running 7.8 km. along the Rideau Canal from downtown to Dow’s Lake recreational area.

My husband and I stayed near Dow’s Lake. When the Skateway opened, we headed out to the lake, eager to glide along the ice. We hadn’t skated in ten years. I laced up my skates, took a step – and retreated to the bench. Ice is slippery. Skate blades are too thin the for support. I don’t want to fall and break a bone. My skating career ended, I consoled myself with a Beavertail. These pastries, sold at shacks on the canal, are fried dough in the shape of Canada’s national animal’s tail topped with anything imaginable. I usually get the Killaloe Sunrise, with cinnamon, lemon and sugar that brings out the flavour of the dough. The calories keep you warm in winter.

|

| Hazelnut spread, peanut butter and Reece’s Pieces on a Beavertail. As a true Canadian, I want to try maple someday. |

Other highlights of Winterlude include dragon boat races on the frozen lake, snow slides in a park on the Quebec side of the river, and an international ice carving contest. Ottawa’s fickle winter weather played havoc with the sculptures this year. A mild spell a few days after the carving competition ruined the ice statues’ delicate features.

|

| A carver at work on downtown Sparks Street. |

Today I write about my visit to Ottawa’s Winterlude this year on the BWL Author BlogSpot.

On Friday, the Calgary central library launched the Print(ed) Word documentary to a celebratory audience. In the film, the twelve artist/writer partners talked about their experiences with this collaborative project. I’m proud to be part of it. My partner, Sylvia Arthur, did a great job of turning my short story, When a Warm Wind Blows Off the Mountains, into an art book. All twelve books are on permanent display in the central library, housed in an alcove off the 4th floor Great Reading Room. For a taste of the works, have a look at the documentary movie trailer.

Here’s my blog post, which appeared on my publisher BWL’s website on Jan 12th.

I enjoy year end lists. Even better are lists at the end of a decade. Here’s my list of five changes to my writing life that happened in the ten years from January 2010 to January 2020.

1. I became a published author. Prior to 2010, I’d published short stories, poems and articles. They all helped me feel like a real writer and led me to teaching writing courses and workshops, but the term ‘published author’ is generally reserved for those who have published a book. This was a milestone I longed to achieve. After years of work, my first novel, was published in spring 2011.

2. I stepped up my social media presence. I was on Facebook before Deadly Fall was published, but only had a small number of Facebook friends, all people I knew in my real life. After my book publication, I started accepting requests from virtual strangers and posted (too many) notices about my literary activities and accomplishments in the interests of promoting the novel. I also joined Twitter and had my son’s friend create my author website, which automatically tweets my website posts. In addition, I’ve dabbled in Link-In, Goodreads, Pinterest and Instagram. It seems that just when I get onto one social media site something else becomes the hot new thing.

|

| Social Media can make me feel pulled in all directions |

3. My office moved to a different room in my house. Okay, I’m cheating here because my home office changed when my husband retired in fall 2007. But it took a few years for us to settle into our new routine. When he was working, as soon as he left for the office I’d go to my den upstairs to write. My retirement gift to him was our den, a sunny spot that looks out to a green space. I moved my work to our north-facing guest room with a street view. I figured that if he had an appealing room for his various computer activities, he wouldn’t distract me from my writing, while I don’t need the view while I’m forming stories in my head. The plan worked. After breakfast these days, he goes to his den and I huddle in the corner of our guest room. But lately, I’ve felt an urge for a brighter, more scenic and spacious room of my own for writing.

| Jane Austen wrote pretty good novels at this small writing table with its view of the clock in the family sitting room. |

4. I became a regular at a writing festival. Calgary’s When Words Collide Festival For Readers and Writers launched in August, 2011. I went the first year, since it’s held in my home city, and haven’t missed a year since then. This coming August will be the festival’s 10th anniversary. I’m bound to find whatever I’m looking for as a writer there, whether it’s information about the craft or getting published or promoting my books. Toss in a little fun for a winning combination.

| Dressed for the festival’s banquet, Roaring Twenties theme |

.

5 At When Words Collide, I found my publisher. BWL published my second and third novels and there’s a fourth one in progress. In November, BWL released a new edition of my first book, retitled A Deadly Fall. The re-publication brings the 2010s full circle and seems a fitting end to the decade.