Suzette Mayr’s novel Monoceros is a Calgary book that I found moving, challenging and memorable.

Category Archives: Blog

Top Earning Writer

Who’s the world’s top earning writer? Clue: he leaves the rest of us in the dust. It’s in this month’s issue of Opal Point of View ezine along with tips for social media, blogging for fiction writers and writing accurate crime scene investigation.

Follow this link to view the February issue

http://www.opalpublishing.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Opal-Point-of-View-February-2016.pdf

You can download a copy of the PDF file from our website www.opalpublishing.ca

|

|

|

|

Copyright © 2016 Opal Publishing, All rights reserved.

Our mailing address is:

McKenzie Towne, Calgary, Alberta

Want to change how you receive these emails?

You can update your preferences or unsubscribe from this list

Shrinks

“Psychiatry enables us to correct our faults by confessing our parents’ shortcomings.” (Laurence Peter)

Jeffrey A. Liberman includes this tongue-in-cheek quote in his book Shrinks: The Untold Story of Psychiatry. Published in 2015, Shrinks comes with Liberman’s strong credentials: Chairman of Psychiatry at Columbia University; Director of the New York Psychiatric Institute.

Like the first psychiatry book I read, Shrinks begins with a reference to the profession’s ongoing tension between nature and nurture; the swings between the belief that mental illness is entirely in the mind and the belief that is in the brain. We must embrace both, Liberman says.

Like the first psychiatry book I read, Shrinks begins with a reference to the profession’s ongoing tension between nature and nurture; the swings between the belief that mental illness is entirely in the mind and the belief that is in the brain. We must embrace both, Liberman says.

Shrinks continues with the history of psychiatry.

An early practioner, Mesmer, believed the cure for mental illness was inducing crisis. He tried to provoke fits of madness in the psychotically ill and bring depressives to the brink of suicide.

Liberman calls Sigmund Freud a tragic visionary, far ahead of his time. Freud’s theories of conflicts between unconsious mechanisms defined mental illness. But Freud’s controlling ways alienated his followers and his theories and methods were unscientific and rigid.

The profession wanted a more solid, medical footing, especially after the anti-psychiatry attacks of the 1960s and 70s.

The popular and acclaimed 1975 movie One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest captured the public view with its portrait of the psychiatric profession as morally and scientifically bankrupt. Liberman doesn’t say this, but I suspect Cuckoo’s Nest played a role in the temporary abandonment of Electroconvulsive therapy (aka Shock Therapy), shown so gruesomely and cruelly in the film. ECT is back with us now as a treatment for depression when medication and/or therapy fail.

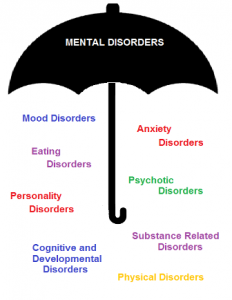

Liberman takes us through the drama of the DSM III, released in 1979. Before reading Shrinks, I was only vaguely aware of The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), called the bible of psychiatry. The DSM is periodically revised and 2013 welcomed the fifth release. But the big change occurred with # 3, which drove the nail into Freudian psychoanalysis by defining mental illness by symptoms and courses of the illnesses, rather than by causes.

DSMs 4 & 5 made some minor changes, which included adding the only two disorders currently defined by cause: Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Substance Abuse.

After reading about the debate, I can see why the DSM definitions matter. Either a disease’s root cause is of vital importance to treatment or its cause is less important than its symptoms. Something is labelled a disease or not. Notoriously, homosexuality was a disorder in the original DSM.

Historically, Liberation says, biological and pschyodynamic theories of mental illness have fared equally well and, today, most psychiatrists address both. From my other readings, though, I get the sense the balance is weighted on the biological side, although not as heavily as it is with the general public. Liberman might not see it so weighted because, despite his initial admiration for Freud, he seems to have landed closer to the biological argument and prescribes medication as a front-line treatment. This isn’t surprising when his speciality is therapy-resistant schizophrenia.

Shrinks struck me as a knowledgeable book written by someone high up in the mainstream of the psychiatric profession. My next readings challenged the conventional point of view.

February is Psychiatry Month

Two-three years ago I read eight books on modern psychology as research for my novel, To Catch a Fox. I posted reviews of the books on my blog and now hate to see all that effort lost in cyberspace. Since the Government of Canada has established February as Psychology Month, I’ve decided to re-run my posts through the month, with the odd updated tweak here and there. I’m finding it interesting to revisit the messages in these books. Here’s the first of the rebooted series:

I began my readings about modern psychology/psychiatry with Psychiatry: A Very Short Introduction by Tom Burns (Oxford Press 2006). The book is short, to the point and provides a good overview for not too much reading effort.

Burns’ introduction spoke to me when he remarked on the current preference to say that psychiatry is “just another branch of medicine.” The goal, he notes, is to raise the status of the profession and reduce the stigma of mental illness. The problem is, psychiatry is different. There are real differences between mental and physical illnesses that won’t go away simply because we want them to.

In Chapter One ‘What is Psychiatry?’ Burns points out that psyche is the Greek word for mind (It’s also the Greek word for ‘soul’ or ‘breath of life’).

While the ancients pondered psychology (human thought and behaviour), the profession of psychiatry developed in the late 19th century with Sigmund Freud’s treatment of neurotic disorders, which he believed were caused by repressed unconsious thoughts.

Freud’s theories contributed much to twentieth century thinking — we still use the term Freudian slip, but his method of psychoanalysis has become increasingly marginalized in modern psychiatric practice. Today’s approach favours quicker and cheaper therapies that work at changing behaviours, with no need to understand underlying issues. Cognitive Therapy, with it’s goal of changing thinking, falls between behavioural and psycho therapy and has become one of the most successful and widely practiced therapies today. For better or worse, many turn to the self-help movement, a modern outgrowth of psychotherapy. Drugs are the cornerstone of treatment for psychotic illnesses, the primary ones being schizophrenia and biopolar disorder.

What’s the difference between neurotic and psychotic? The latter involves a loss of insight into the personal origins of one’s strange experiences; an inability to reality check.

As I learned on the Internet, the the newer drugs developed to treat neurotic disorders like depression aren’t more effective than the older ones. They work better because their fewer side effects make people less inclined to discontinue them. The newer drugs are more expensive to develop and produce. Some critics claim this encourages pharmaceutical companies to push agendas to redefine conditions we once viewed as normal as an illness. While it is good to recognize certain conditions, Burns observes that the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) definition of Oppositional Defiant Disorder sounds a lot like difficult teenager.

His book reminded me of the anti-psychiatry movement that was popular on college campuses in the 1960s and 70s. I never got past the title of Thomas Szasz’ book The Myth of Mental Illness, but discussed his message that the schizophrenia is just a different take on the world. Szasz, R.D.Laing and others battered the psychiatry profession during these decades and their views carry forward with the Scientologists. Burns suggests, in general, there is less opposition to the concept of psychology and psychiatry today, possibly due to an exaggerated faith in biological explanations.

The nature vs. nurture debate is inherent in psychiatry. Freud’s theories and approach shifted the focus to nurture, even though he believed that medicines would ultimately be the cure. The nurture view prevailed from the 1940s to 1970s. The upside of nurture is the possibility of cure; the downside is blame, especially to parents.

Why do parents blame themselves? Because we need to believe we have influence to invest all that time in child raising. It’s evolutionary.

The conclusion of Burns’ book brings us back to the start: the mind is not the same as the brain. Psychiatry isn’t just another branch of medicine. When people can choose, they usually want a mixture of medicine and therapy.

Mental illness is still defined by its impact on the person’s sense of self and on his or her closest relationships. As Freud put it, his goal was to enable people to work and love.

Water and Waves

When I saw this picture on Calgary Through the Eyes of Writers I thought it was waves on a Mexican beach. Turns out it’s ice on the Bow River.

Research Time

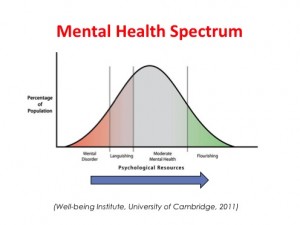

After I finished my NaNoWriMo writing project in November, I felt a need to update myself on mental health treatment, which is a topic of both the NaNo memoir and the novel manuscript I completed earlier this fall. Like most of us these days, I turned first to the Internet.

I found pages of stats:

One in five Canadians has a lifetime chance of mental illness, according to The Mood Disorders Society of Canada. 10.4 % of Canadians has a mental illness at any given time. This jibes with statements that one in ten Americans are taking antidepressants, the most prescribed medication in the USA. World-wide, depression is the leading cause of disability. The statistics go on and are, well, depressing.

I found information that surprised me:

Today’s antidepressants are no more effective than their counterparts in the 1970s, despite the billions spent on research and development during the past forty years. The newer drugs simply have fewer side effects, which makes people more inclined to continue taking them. Drug treatment is still hit and miss. No one really knows why antidepressants work. Many question if they work at all. A 2011 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that, while meds appear to benefit severe depression (about 1/3 of cases), for mild to moderate depression they are no more effective than placebos.

Evidence suggests that some kinds of therapy, notably Cognitive Therapy, work better than medication, especially for preventing relapse. Therapy combined with medication works best.

The rate of relapse for severe depression is 50-90 percent, depending on which website you read, with a lifetime average of four episodes per person. This is far, far from a cure.

Scans show that depressed brains look different than normal ones. It’s unknown if this altered brain chemistry causes depression or is an effect of it.

Is mental illness caused by biological, psychological, environmental or other facters, or a combination of these? The debate continues.

This preliminary research made me want to dig deeper, so I went to my library website and put holds on books about psychology and psychiatry that seemed relevant. Notices quickly appeared in my email inbox and I’ve now read five books, with more to come. Most of these books took me through the history of psychiatric treatment, which has been with us for less than two hundred years. They also provided different opinions on current treatments. Extremely different opinions in some cases.

To help me wrap my head around these readings, my next blogging project will be weekly reviews of these books. Tune in next week for my take on: Psychiatry: A Very Short Introduction by Tom Burns.

Diversity

Since I moved to Calgary almost 20 years, the city has become much more ethnically diverse. This is reflected by newer Calgary writers, notably Anita Rau Badami.

Boom & Bust

It’s interesting to feel the mood of Calgary in the late 1970s during this current mood of ‘bust’, if we dare use this dreaded b-word. On the plus side, my city taxes are lower this year.

Literary Map of Canada

Here’s a fun start to the new year – a literary map of Canada, 1936. Calgary is called Calgary Station and the map is full of rustic Canadian images. I confess I hadn’t heard of the four Calgary writers. I also hadn’t heard of most of the Canadian ones either. Such is the lasting fame of most writers.

Yes

A poet says yes to Calgary on a cold, winter day when the city is reeling economically.