Two-three years ago I read eight books on modern psychology as research for my novel, To Catch a Fox. I posted reviews of the books on my blog and now hate to see all that effort lost in cyberspace. Since the Government of Canada has established February as Psychology Month, I’ve decided to re-run my posts through the month, with the odd updated tweak here and there. I’m finding it interesting to revisit the messages in these books. Here’s the first of the rebooted series:

I began my readings about modern psychology/psychiatry with Psychiatry: A Very Short Introduction by Tom Burns (Oxford Press 2006). The book is short, to the point and provides a good overview for not too much reading effort.

Burns’ introduction spoke to me when he remarked on the current preference to say that psychiatry is “just another branch of medicine.” The goal, he notes, is to raise the status of the profession and reduce the stigma of mental illness. The problem is, psychiatry is different. There are real differences between mental and physical illnesses that won’t go away simply because we want them to.

In Chapter One ‘What is Psychiatry?’ Burns points out that psyche is the Greek word for mind (It’s also the Greek word for ‘soul’ or ‘breath of life’).

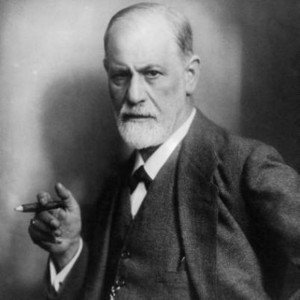

While the ancients pondered psychology (human thought and behaviour), the profession of psychiatry developed in the late 19th century with Sigmund Freud’s treatment of neurotic disorders, which he believed were caused by repressed unconsious thoughts.

Freud’s theories contributed much to twentieth century thinking — we still use the term Freudian slip, but his method of psychoanalysis has become increasingly marginalized in modern psychiatric practice. Today’s approach favours quicker and cheaper therapies that work at changing behaviours, with no need to understand underlying issues. Cognitive Therapy, with it’s goal of changing thinking, falls between behavioural and psycho therapy and has become one of the most successful and widely practiced therapies today. For better or worse, many turn to the self-help movement, a modern outgrowth of psychotherapy. Drugs are the cornerstone of treatment for psychotic illnesses, the primary ones being schizophrenia and biopolar disorder.

What’s the difference between neurotic and psychotic? The latter involves a loss of insight into the personal origins of one’s strange experiences; an inability to reality check.

As I learned on the Internet, the the newer drugs developed to treat neurotic disorders like depression aren’t more effective than the older ones. They work better because their fewer side effects make people less inclined to discontinue them. The newer drugs are more expensive to develop and produce. Some critics claim this encourages pharmaceutical companies to push agendas to redefine conditions we once viewed as normal as an illness. While it is good to recognize certain conditions, Burns observes that the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) definition of Oppositional Defiant Disorder sounds a lot like difficult teenager.

His book reminded me of the anti-psychiatry movement that was popular on college campuses in the 1960s and 70s. I never got past the title of Thomas Szasz’ book The Myth of Mental Illness, but discussed his message that the schizophrenia is just a different take on the world. Szasz, R.D.Laing and others battered the psychiatry profession during these decades and their views carry forward with the Scientologists. Burns suggests, in general, there is less opposition to the concept of psychology and psychiatry today, possibly due to an exaggerated faith in biological explanations.

The nature vs. nurture debate is inherent in psychiatry. Freud’s theories and approach shifted the focus to nurture, even though he believed that medicines would ultimately be the cure. The nurture view prevailed from the 1940s to 1970s. The upside of nurture is the possibility of cure; the downside is blame, especially to parents.

Why do parents blame themselves? Because we need to believe we have influence to invest all that time in child raising. It’s evolutionary.

The conclusion of Burns’ book brings us back to the start: the mind is not the same as the brain. Psychiatry isn’t just another branch of medicine. When people can choose, they usually want a mixture of medicine and therapy.

Mental illness is still defined by its impact on the person’s sense of self and on his or her closest relationships. As Freud put it, his goal was to enable people to work and love.