Lori Hahnel’s short story “Good Friday, at the Westward captures a past music scene in Calgary. How fitting for this week of featuring the Juno Awards in Calgary.

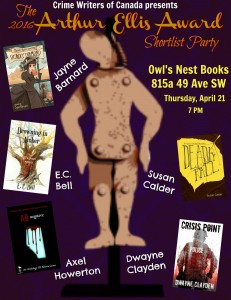

Arthur Ellis Shortlist Awards

I’m excited to be hosting this year’s Arthur Ellis Shortlist Event in Calgary, featuring Crime Writers of Canada authors Jayne Barnard, E.C. Bell, Dwayne Clayden and Axel Howerton. Join us for a night of conversation, fictional shenanigans, criminal mischief and the announcement of this years official nominees for the 2016 Arthur Ellis Awards, honoring the the best of this year’s Canadian crime writing!

I’m excited to be hosting this year’s Arthur Ellis Shortlist Event in Calgary, featuring Crime Writers of Canada authors Jayne Barnard, E.C. Bell, Dwayne Clayden and Axel Howerton. Join us for a night of conversation, fictional shenanigans, criminal mischief and the announcement of this years official nominees for the 2016 Arthur Ellis Awards, honoring the the best of this year’s Canadian crime writing!

When? April 21, starting 7:00 PM

Where? Owl’s Nest Bookstore, Brittania Shopping Centre, 815A 49th Avenue SW, Calgary

Weaselhead

My Wednesday morning walking group went to the Weaselhead in early March. Here’s poet Stuart Ian McKay’s impression of this iconic Calgary location. Our group’s March morning was icy in the Weaselhead. Rather than slip all over the place, we went up to the North Glenmore ridge with its dry path and views of the reservoir and mountains.

Open Heart

Before I read her memoir Open Heart, Open Mind, I knew Clara Hughes as the Canadian Olympic speedskater with the big smile.  I was impressed when I heard that after retiring from speedskating, she would pursue Olympic cycling. Tackling two Olympic sports, a summer and winter one. Wow.

I was impressed when I heard that after retiring from speedskating, she would pursue Olympic cycling. Tackling two Olympic sports, a summer and winter one. Wow.

I had forgotten or wasn’t aware that Clara had started her sports career with cycling, primarily long-range endurance road cycling. Her memoir describes its dangers, such as the moment you’re speeding up or down a mountain and a vehicle appears from nowhere. A colleague’s death in a bike race prompted Clara to leave cycling for her first sports love — speedskating, which had been inspired by Gaetan Boucher’s skating at the Calgary Olympics. After winning a fist full of skating medals, she wrapped up her Olympic career with a second ride at cycling.

It wasn’t an easy road to the podiums. I’m sure it isn’t for anyone, but Clara’s life might have easily spiralled in the opposite direction. Her father was an alcoholic, quick to anger and verbally abusive to his wife and two daughters. Clara’s mother, the daughter of an alcoholic, divorced her husband when Clara was young. As teens, Clara and her older sister acted out, drinking, smoking, partying and sleeping around. Her sister sank into severe depression, from which she never fully recovered. At the time of writing, she was living in a long term care facility.

Clara was rescued by sports. Her first cycling coach was harsh. He drove her to excellence, while undermining her self-esteem. Ultimately, she dropped him, but credits him for her early accomplishments. This is a feature I admire about the book. Clara doesn’t portray the people in her life as black and white characters. Her father could be cruel — he called her less successful sister ‘the other one’ rather than refer to her by name — but Clara often looked to him for advice. Several times he guided her through a difficult issue.

Clara had luck – her athletic gift. She had and has drive. She managed to find her perfect mate. Athletic and free-spirited, Peter supported her through her grueling sports competitions and beyond.

Clara had luck – her athletic gift. She had and has drive. She managed to find her perfect mate. Athletic and free-spirited, Peter supported her through her grueling sports competitions and beyond.

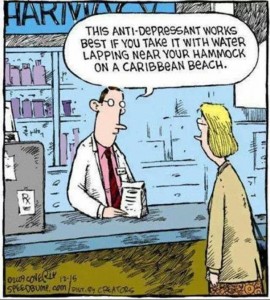

In the midst of riding and skating to the top, Clara suffered from recurring depression and related problems, such as over eating. This is another thing that struck me about the memoir. After reading my six psychology books this winter, it stood out that Clara consistently attributes her problems to her family and sports situations, not biology. Only toward the end of the memoir does she concede there is likely a genetic component to her problems, given her multi-generational history of alcoholism and psychological issues, but this doesn’t matter. She prefers to seek solutions without medications which, she feels, are more likely to mask than treat symptoms. In addition to lifestyle changes, she tried an unorthodox therapy approach that she believes worked.

Reaching out might help her too. She has donated winnings and loaned her name to two causes dear to her heart: Mental Health and Kids Can Play, a project devloped by an Olympic colleague that improves life for children in third world countries through playing.

Clara is a champ on every level.

Restless

Aritha Van Herk’s novel Restlessness set in Calgary and published in 1998 is timely, given the current Canadian debate over assisted dying.

Athletes and March Chinooks

I’m reading Clara Hughes’ memoir Open Heart, Open Mind, so this excerpt from Angie Abdou’s novel The Bone Gage about another Olympic contender spoke to me. Abdou also nailed the mood of Calgary during a March chinook, but I hope we won’t see minus twenty again this season. Actually, have we seen it yet this year?

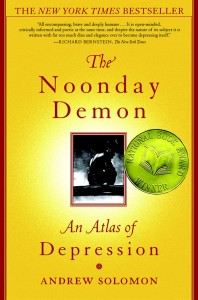

Demon

My reading about modern pschology and psychiatry continued with The Noonday Demon: an Atlas of Depression by Andrew Solomon. I chose this book because a couple of my earlier readings mentioned it, with praise.

Demon differs from the other five books I’ve read for several reasons. The author, Solomon, is a writer, not a medical expert. While the other books dealt with mental illness, in general, Solomon focusses on depression, from which he has suffered on and off for seven years (as of 2001, the year of the book’s publication). Solomon did extensive research to write the book, as evidenced by the 100 pages of footnotes and bibliography at the end. Demon is part memoir, part medical information, and part life stories of depression sufferers, many of whom contacted Solomon after an article he wrote about his depression was published in the New Yorker in 1998.

Solomon states up front that he disagrees with the current fashion of opposing medication treatment for depession because his father had a lifelong career in the pharmaceutical industry. As a result, Solomon can view the pharmaceuticals as both capitalist and compassionate, with a genuine desire to cure.

Given the vast numbers of antidepressant prescriptions issued today, as in 2001, I don’t know if I’d call an anti-medication view fashionable. Solomon’s pro-meds view comes out through the book when he criticises doctors and patients who favour going off medication once the person feels well, with relapse as a frequent result.

Solomon, himself, suffered his first breakdown when he was 31, following his mother’s death. Already in psychoanalysis, he sought treatment with medication, recovered, broke down a second time, recovered, and suffered a mini-breakdown before completing the book a year later. As a result, his descriptions of his own experience is detailed and fresh. At the time of writing, he was taking about 12 pills a day, some for side effects of his antidepressant and anxiety meds, and expected to continue on a cocktail of medication for life. He accepts the genetic view of mental illness and all his life story cases portray it as a lifelong disease. This would be my main quibble with the book: there is no sense that someone might recover from this demon state until the distant day some major physical treatment is found.

When The Noonday Demon was published, Solomon was 38 years old. He wrote in the book that he was fine with popping pills for life even though he knew they wouldn’t completely do the trick. It beat the alternative of more frequent and severe breakdowns. He’s now 52, and doing well, from my brief Google search. He’s married, with kids, still writes articles and books and is a professor of clinical psychology at Columbia University. (Did he get that post because of his book or a degree?) I’d like to know if he’s still taking multiple medications and still relapsing regularly into depression and, if so, is he still okay with this after sixteen years? I think some of his opinions in Demon might have benefitted from a delayed perspective.

The Noonday Demon is a big book, large in scope and information. The medical details are as sound as any I’ve read written by practicing psychiatrists and psychologists; Solomon’s opinions as valid as any expert’s, partly because there is no final word on mental illness. Solomon provides many extras the other experts don’t go near. He travelled far and wide to research alternative treatments and try them personally. An exorcism in Africa involved him hugging a ram, the two of them buried under layers of covers, before the ram was sacrificed, its blood drenched over Solomon’s body.

The Noonday Demon is a big book, large in scope and information. The medical details are as sound as any I’ve read written by practicing psychiatrists and psychologists; Solomon’s opinions as valid as any expert’s, partly because there is no final word on mental illness. Solomon provides many extras the other experts don’t go near. He travelled far and wide to research alternative treatments and try them personally. An exorcism in Africa involved him hugging a ram, the two of them buried under layers of covers, before the ram was sacrificed, its blood drenched over Solomon’s body.

Solomon was open enough to find merit in most of these treatments, however unusual, although he didn’t suggest that any could compete with medication, ideally supplemented with psychoanalsis. His view of his fellow sufferers in the case histories is sympathetic. I was surprised, though, that after those hours of hugging, he didn’t show more sympathy toward the poor ram that was sacrificed to exorcise Solomon’s demons.

Heralding Rosalie and Rose

As a regular reader of The Calgary Herald, I was interested this story by author Katherine Govier involving the newspaper.

Curiously, today’s Calgary Herald features author Joan Crate’s new novel Black Apple that bears similarities to Govier’s book. Both deal with First Nations issues and have a protagonist named Rose or Rosalie.

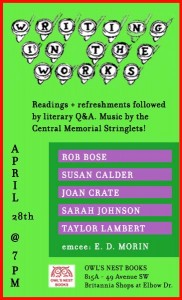

Joan’s book launch is this Tuesday, March 1, at Shelf Life Books.  I look forward to reading with Joan on April 28th at Writing in the Works at Owl’s Nest Bookstore.

I look forward to reading with Joan on April 28th at Writing in the Works at Owl’s Nest Bookstore.

Spellbinding

I saved Brain-Disabling Treatments in Psychiatry: Drugs, Electroshock and the Psychopharmaceutical Complex by Peter R. Breggin, MD for the last of my five readings on psychiatry because the book is long – 450 pages – and the title sounded technical. Breggin states at the start that the book is aimed at professionals, although he hopes it’s clear enough for non-professionals to understand.

I saved Brain-Disabling Treatments in Psychiatry: Drugs, Electroshock and the Psychopharmaceutical Complex by Peter R. Breggin, MD for the last of my five readings on psychiatry because the book is long – 450 pages – and the title sounded technical. Breggin states at the start that the book is aimed at professionals, although he hopes it’s clear enough for non-professionals to understand.

Partly for this reason, I only read the first and last sections, along with the brief conclusions he sometimes offered for the middle sections. This was enough to convince me that, of the five books I read, this is the one I have the most affinity with. It also did the most to change my thinking on mental health treatment.

Breggin, age 79, has been a practicing psychiatrist in upstate New York for over 40 years. He claims he has never prescribed medication and has never lost a person to suicide. He disagrees with the biological model for mental illness and avoids labels such as schizophrenia and biplolar disorder. His approach is to listen to a patient’s life story. That is, to treat him or her as a person and not as a problem to fix.

Breggin, age 79, has been a practicing psychiatrist in upstate New York for over 40 years. He claims he has never prescribed medication and has never lost a person to suicide. He disagrees with the biological model for mental illness and avoids labels such as schizophrenia and biplolar disorder. His approach is to listen to a patient’s life story. That is, to treat him or her as a person and not as a problem to fix.

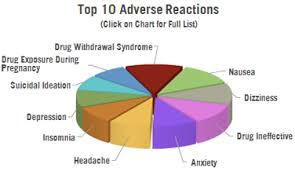

The part that threw me the most is his belief that psychiatric drugs are not only ineffective, they are harmful and work against recovery by impairing mental and emotional function. People’s belief these medications are helping them are due to the drugs’ spellbinding effect, much like the belief that you are witty and in control when drunk.

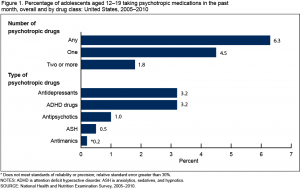

The large middle section of his book is devoted to proving his point for each current treatment, including psychotropic drugs, Electro Convulsive Therapy (ECT or Shock Therapy) and the medications for Attention Deficit Disorder. He especially opposes the current treatment of children for ADD/ADHD and depression. He claims there is an upsurge in diagnoses for bipolar disor today because antidepressants have caused mania in people, who are then told by their psychiatrists that the treatment has unearthed this underlying condition.

I don’t feel qualified enough to know if his arguments against these treatments are solid or not. This is a second reason I skipped over the book’s middle. A third is that I don’t need his detailed arguments to be convinced, since I favour the nurture, rather than nature, view of mental illness and can easily accept a critique of medication. Breggin states that even if it is one day proven that some disorders are due to chemical imbalances — and there is no proof for this so far — our current drugs and shock therapy aren’t the way to go.

His extreme views made me Google him to find out if he’s a Scientologist, since they are notoriously opposed to modern psychiatry and its treatments. Breggin was associated with the Scientologists in the early 1970s, but wasn’t a member, although his wife was. He broke with the the religion partly because they opposed her marriage to an outsider. No doubt Scientology’s views on psychotropic medication were an attraction for him and the religion might have influenced, or at least reinforced, his thinking. Pharmaceutical companies have accused Breggin of being a Scientiologist to discredit him because he has been an expert witness in lawsuits against their products and vocal in his opposition to them.

Breggin wrote a defense of Tom Cruise’s rants on TV against psychiatry and medication. “The media would have liked to attack Tom on the grounds that he’s a Scientologist,” Breggin says. “Scientologists seem to share a number of views about psychiatry with me, including everything Tom said. In fact, I’d go further. Modern biological psychiatry is a materialistic religion masquerading as a science.”

Breggin’s credentials and clinical experience make it hard to dismiss him as a quack.  I was moved by the final section of his book, where he outlines his 20 tips for an empathetic psychiatry. He notes these guidelines could also be used in our everyday lives with colleagues and friends, and insists they have worked in his psychiatric practice, even with the most difficult and psychotic cases.

I was moved by the final section of his book, where he outlines his 20 tips for an empathetic psychiatry. He notes these guidelines could also be used in our everyday lives with colleagues and friends, and insists they have worked in his psychiatric practice, even with the most difficult and psychotic cases.

Psychosis, he says, is a “loss of connectedness to other human beings. The individual who withdraws into a fearful, self-protective, irrational fantasy responds best to being treated with kindness, respect, and the gradual building of rapport.”

It seems naive, and yet I can see the approach working with one such person I know. I intend to apply it in the future.

Arrival

I got back this week from a four week trip to Mexico and can relate to David Albahari’s experience of a foreigner thrust into Calgary. I’m still a little zoned out.