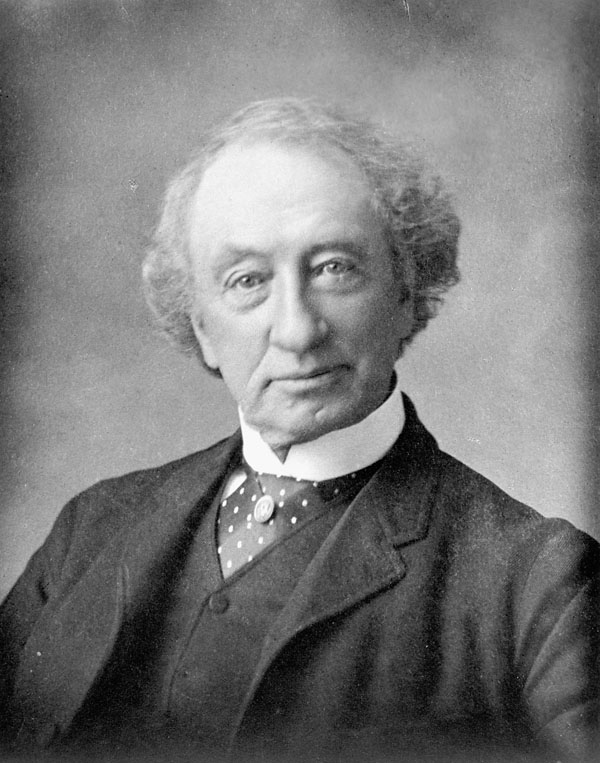

Last summer I took out a library book about Canada’s first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, because I wanted to know if modern historians have changed their view of him since my high school history class in the 1960s. Back then we learned Macdonald was flawed and made mistakes, but Canada would be considerably less without him.

Macdonald’s government established the residential schools that caused a century of suffering to indigenous children. The effects continue today. To protest the history and present situation, people have vandalized statues of Macdonald across the country. Cities have responded by removing the statues and looking into renaming buildings and other structures bearing Macdonald’s name. As one journalist wrote, ‘Would you want your child to attend Adolph Hitler High School?’

In the Calgary Public Library, I found a book that sounded like what I wanted: Macdonald at 200: New Reflections and Legacies, edited by Patrice Dutil & Roger Hall (Dundurn Press, 2014). This collection of 15 essays by historians, other academics, and journalists promised a fresh look at Macdonald on the 200th anniversary of his birth in January 2015. I began by looking up ‘residential schools’ in the book’s index, figuring I’d read those sections first. The schools weren’t listed in the index. Already this six-year-old book felt dated. I can’t imagine a current book about Macdonald not giving prominence to the subject. Only two of the fifteen essays mentioned the residential schools, one peripherally.

In contrast, a number of the essays discussed Macdonald’s treatment of women, a more popular issue for readers in 2014. The consensus was that Macdonald’s view of women was enlightened for his era. For instance, when he was first elected prime minister in 1867, only non-indigenous men who owned property were allowed to vote. Years before the suffragette movement, Macdonald proposed extending the franchise to female property owners. The opposition party voted this down, but Macdonald succeeded in getting the vote for indigenous men who owned property, while allowing them to retain their full Indian status benefits. This took considerable persuading. After Macdonald’s death, the opposition came into power and repealed the law. Status Indians didn’t regain the right to vote until 1960.

The one essay that examined the residential schools confirmed the protesters’ main message: part of Macdonald’s goal for the schools was to speed up the assimilation of indigenous peoples by removing children from their culture. For that reason, he insisted girls attend as well as boys, in the belief women had more influence in home life and ‘uneducated’ girls would drag their children back to the old ways. While protesters would disagree, education was another goal for the schools, to give indigenous people the skills to become self-sufficient after the loss of the bison hunt. Most of the treaties specified that Canada must provide a European education and the chiefs initially wanted this for their people until they saw how the system worked. As we sadly know now, this attempt at forced assimilation was wrong. But how many non-indigenous Canadians realized this at the time? Aren’t the governments that followed Macdonald’s equally guilty for continuing the residential school system with no significant changes until 1948, when they made attendance at residential schools non-compulsory.

Why is Macdonald singled out for attack? I will take a leap and say it’s because, of all our prime ministers, he most represents Canada. He was the leader of the Fathers of Confederation at the Charlottetown conference in 1864. He was our first prime minister and the second-longest serving (18 years, 359 days; six majority governments). His push to build the railroad to the Pacific coast probably prevented the west from joining the United States. According to Macdonald at 200, souvenirs with his image are more popular with Ottawa tourists than those of any other prime minister. Macdonald is interesting. In high school, we learned he was a drunk who famously quipped that voters would prefer Macdonald drunk to his opponent sober. Macdonald at 200 rehabilitates him by claiming he was binge drinker, but eventually overcame his problem and should be admired for this.

One of the last essays in the book discusses how Macdonald is remembered through statues and naming. The author observes that Canadians tend to revere their political leaders far less than Americans. Macdonald’s US counterpart, George Washington (a slaveowner) has the country’s capital city district and a state named for him, among hundreds of other things. The essay also notes that the way historical figures are honoured (or not) says less about them than it does about the people doing the remembering. Macdonald’s political opponents were the first group in charge of his legacy and were inclined to diminish his accomplishments. We have every right today to diminish Macdonald further to uphold our current values.

Overall, I’d say the book’s message didn’t significantly change my former view of Macdonald. He was flawed, he made mistakes, he accomplished great things if you believe Canada is a worthy country. From their biographies, none of the fifteen essay authors identify as indigenous. After investing years of research on Macdonald, they’d be predisposed to come down on his side. One author concluded indigenous people would probably have been worse off without him. Another called for a full study of Macdonald’s relationship with indigenous people. Both politically and personally, Macdonald’s involvement with indigenous Canadians was the most extensive of our prime ministers. I would read a book about that.